A Nazi War Train Hauled the Biggest Gun Ever Made

World War II was the twilight of railborne artillery

by JAMES SIMPSON

War trains dominated combat for more than 100 years. Massive rail-borne artillery shelled the enemy while trains unloaded troops and supplies. For a brief moment, the terrifying machines were the most powerful weapon on the battlefield. But technology advanced.

Improvements to tanks, cars and planes during World War II marked the twilight of the war train. The great trains of World War I still dominated the imagination, however, and the Nazis built impressive—but impractical—railborne cannons.

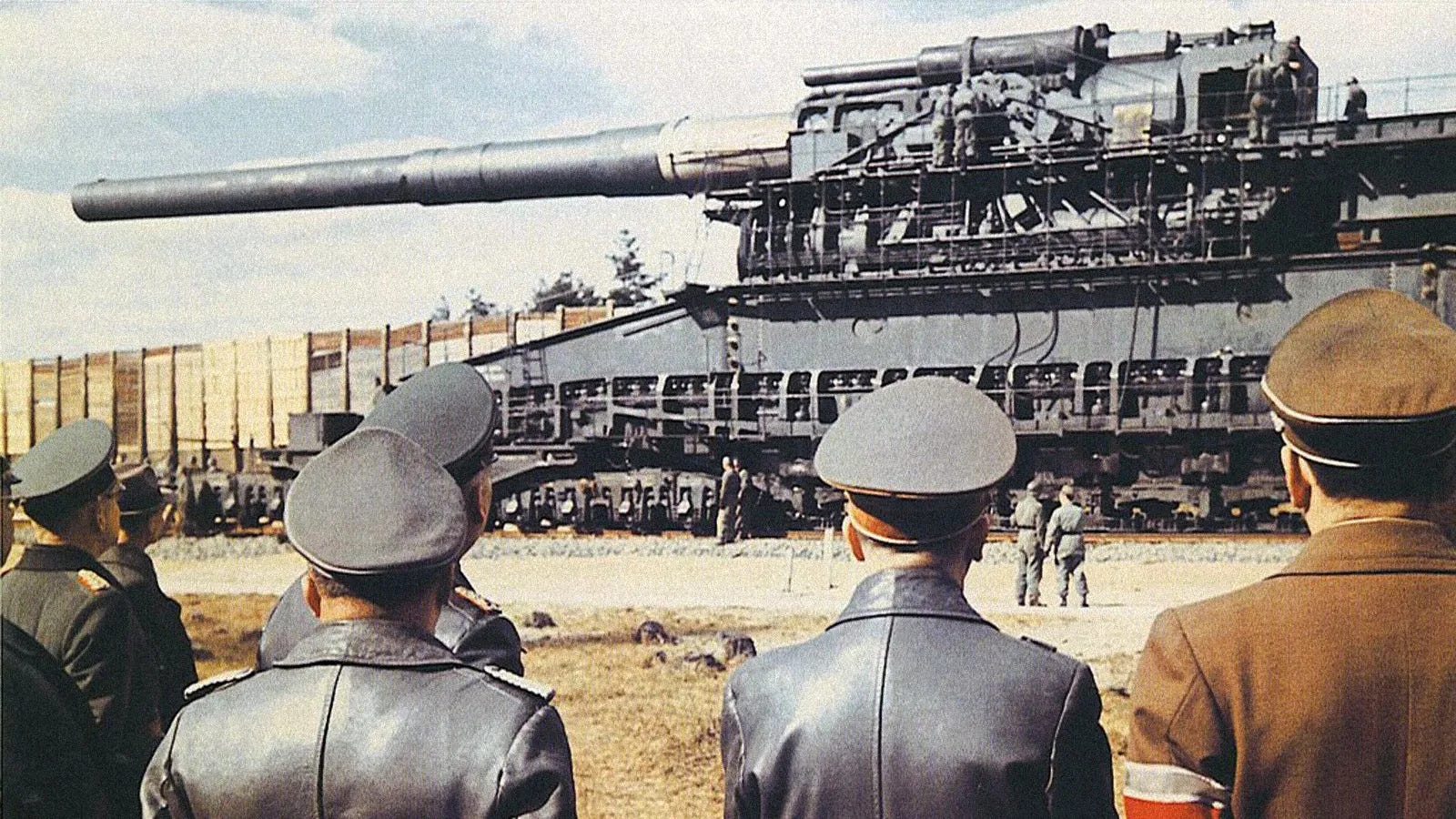

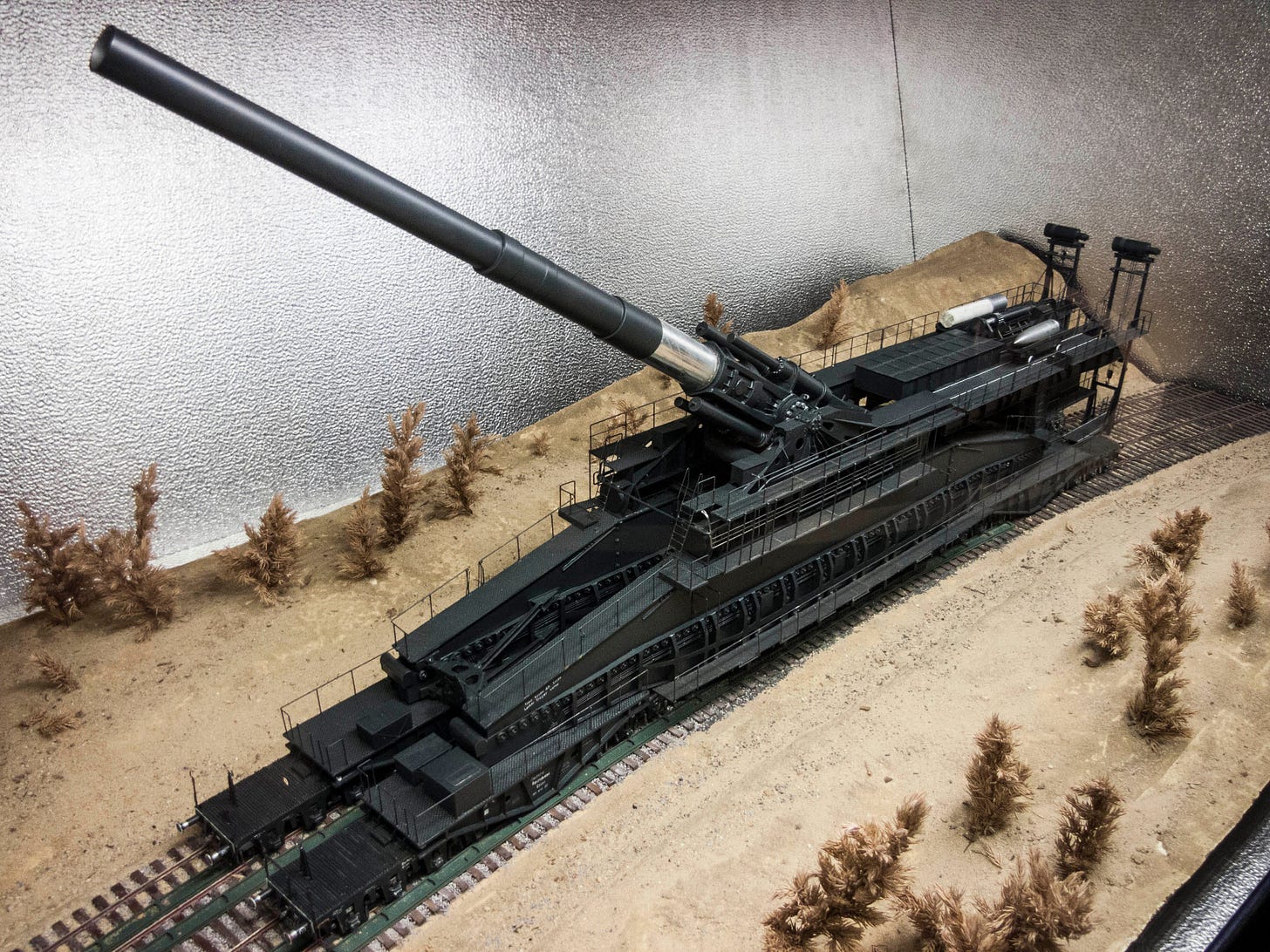

The German Heavy Gustav was the largest gun ever built. It was more than 150 feet long, 40 feet tall and weighed almost 1,500 tons. The steel giant Krupp A.G. made only two, and neither worked well.

The weapon derived from experience. After witnessing the success of other railway guns, the German High Command asked Krupp’s engineers to design a weapon to destroy the French border fortifications along the Maginot Line.

The Gustav’s barrel alone was more than 100 feet long and fired 31-inch-wide, 12-foot-long shells at an effective ranges of 20 miles. The ammo came in two varieties—a five-ton explosive round and a seven-ton armor-piercer.

But the impressively massive superweapons were dinosaurs. It was too bulky, took too long to fire and required hundreds of troops to operate. For centuries, better artillery meant bigger artillery, but that changed during World War II.

Decades of history led up to the Heavy Gustav—successively larger and heavier railway guns leading to the biggest of them all.

The Confederacy deployed the world’s first railway gun during the American Civil War. The rebels attached a naval artillery cannon to a chassis and used it to harry the Union during the Battle of Savage’s Station.

During World War I, the Entente powers converted large naval guns and defensive cannons into railborne artillery to pound German fortifications along the Western Front. Germany had its own fleet of long-range artillery pieces and the Entente powers soon feared the thundering crack of the Paris Gun.

This 211-millimeter cannon bombarded Paris with 243-pound shells from 75 miles away. Each shot took up to three minutes to reach its target as the shell soared through the stratosphere. The gun rode the rails, but could only fire from special concrete firing installations.

On Good Friday, 1918, one of the gun’s shells landed on a church in Paris and killed 91 people. It was a fluke—the gun had a targeting tolerance measured in miles. The citizens of France feared German Zeppelins were dropping bombs on them from the sky.

The Paris Gun was a morale-breaking precursor to the terrifying V-weapons of World War II. It also inspired a new generation of German heavy artillery—including the Gustav—during the interwar period. The Treaty of Versailles, which ended World War I, specifically banned heavy artillery and required the German government to hand over a complete Paris Gun.

The government didn’t comply. Instead, Krupp’s engineers refined the design. They fixed the barrel, expanding the caliber from 21 to 28 centimeters. This improved the accuracy but reduced the range from 80 miles to a still-impressive 40 miles. Krupp called the refined gun the K-5.

Krupp pushed more than 20 K-5s into service beginning in 1936. American troops faced two—nicknamed Robert and Leopold—during the January 1944 amphibious invasion of Anzio, Italy. The 218-ton monstrosities destroyed more than 1,500 tons of ammunition, damaged Allied ships and fired more than 5,500 shells onto the American beachhead.

The Paris Gun and its successor could only fire straight ahead, required engineers to lay down curved tracks to help aim the weapon and took several minutes to reload. Despite these problems, the guns were a devastating success.

The Heavy Gustav was not.

France poured money and concrete into fortifying the Franco-German border in 1934. Berlin needed a weapon to bust the Maginot bunkers and it commissioned Krupp to build it. Krupp’s solution was the Heavy Gustav, a gun so massive it had to run on twin sets of tracks.

Hitler approved the the production of the first Heavy Gustav in 1937 and allocated 10 million Reichsmarks—about $67 million today—to the project.

The Fuhrer asked Krupp to finish the weapon by Spring 1940 for the planned invasion of France, but the sheer technical capabilities required to forge the enormous barrel held the project back until 1941.

France had fallen and the Wehrmacht never needed a supergun to defeat the Maginot Line—they simply skirted around it, as they had in the previous world war. But Hitler now had the world’s largest artillery piece and he intended to use it. In the summer of 1941, Hitler launched his ill-advised invasion of the Soviet Union.

Sevastopol—an important port city in Crimea—was one of the invasion’s key targets. It was Russia’s naval gateway to the Mediterranean and the Tsars spent much of the 19th century fighting over and fortifying the city. Now the Soviets’ defensive citadels were perfect targets for the Heavy Gustav.

Deploying the gun was a labor intensive nightmare. The technical and logistical limitations of the gun restricted its use.

The Wehrmacht located an effective firing site in range of the targets and shipped the weapon to Crimea in pieces aboard 25 trains. Around 3,800 men spend four weeks preparing the site, including excavating a 26-foot tunnel to shelter the weapon between shots.

The weapon needed a crew of 250 soldiers and engineers just to fire its gun. Assembling it required 1,250 engineers, scientists and guards working for three days on top of specially-built double rail tracks.

What the army got for this trouble was a weapon that could fire around 14 times a day. After about 300 shots, the enormous barrel needed replacing, which meant another shipment from Krupp’s factories back in Germany.

The Heavy Gustav fired a total of 48 shots at Sevastopol, mostly on Soviet forts. It never fired in anger again. Berlin blew more than 1,000 tons of steel, thousands of man-hours and millions of Reichsmarks for just 48 shots in a war where steel, labor and treasure were in limited supply.

In other words, it was a technical marvel but a military folly. In the years to come, rockets, atomic weapons and heavy bombers would offer the same functions as the Gustav with greater mobility, range and firing rates.

The Heavy Gustav and the K-5s were the last hurrah for the railway gun and the train as a weapon of war.

Even in the immediate years after World War I, armored trains carried raiding parties which used the vehicles as mobile bases. Now they were obsolete because of the increased efficiency of free-roaming wheeled and tracked vehicles. But the train’s use as a tactical platform continued throughout World War II.

The Germans faced armored trains in Poland, Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union from 1939 to 1941, and deployed armored trains of their own. As in the previous war, the German army pressed captured enemy trains into service.

Both the Germans and Russians found armored trains far more useful as air-defense and rear-line platforms. For the invading German army, they also proved useful in anti-partisan units. Yet Berlin was skeptical of armored trains until 1943, when the war turned against it and the defensive role of war trains suddenly became important.

Infrastructure had always limited the war train. Armored trains were effective at protecting railroads … and not much else. By World War II, tracked vehicles suffered from no such limitations. With their tracks spreading the load of their heavy armor and guns, these vehicles could traverse desert, mud and asphalt alike.

Without a fixed route, tracked and wheeled vehicles were less vulnerable to ambush and sabotage.

With the freedom to operate alongside infantry anywhere in the battlefield, mechanized warfare had matured. Trains had always been good at delivering troops, but soldiers could now be efficiently and quickly carried far from the railroads in trucks and armored personnel carriers.

The rise of air power was the last nail in the war train’s coffin.

On a tactical level, ground attack aircraft such as the Ju-87 Stuka could now carry bombs powerful and accurate enough to destroy railways far from the front lines. On a strategic level, the Allies targeted rail infrastructure as a way to slow military movement and damage industrial capacity. Even giant weapons such as the Heavy Gustav had to factor in the threat of aerial attack and hide in tunnels when not in use.

Aircraft even offered a new means of quickly deploying troops over long distances. On D-Day, the Allies dropped 31,300 paratroopers into Normandy. The USAAF had demonstrated how effective the airlift of supplies could be as it transported hundreds of thousands of tons to the war effort in China.

But in the fight for logistical dominance, the railway was still essential for continental transport of supplies and personnel—and enabling the Reich’s atrocities. The German railroad was responsible for enabling the full industrial-scale horrors of the Holocaust, as some four of six million victims traveled to concentration camps aboard the Reich’s railway network.

At the same time, railroads were partly responsible for ending the war. Britain’s railways delivered the pipelines to transport fuel across the Channel, the floating concrete harbors to carry armor to the beaches and the millions of troops needed to end the German occupation of Europe.

There is still nothing like the railway for continental logistics. Even today in the age of heavy-lifting aircraft, trains supply arms to Russian troops in Ukraine. The rails may no longer carry the massive weapons of war, but they still play a crucial logistical role that’s often overlooked.

Read more: