Black & Defiant

Eugene Bullard was a fighter pilot, boxer, musician, spy and civil-rights activist

by SEBASTIEN ROBLIN

In September 1917, Eugene Bullard was at the controls of his Spad biplane, flying a patrol over Verdun in northern France with the French air force’s N.85 Escadrille.

Thousands of feet above a war-torn moonscape of trenches, barbed wire and craters, the pilot later dubbed “Black Swallow of Death” spotted a formation of blood-red, triple-wing fighter planes barreling toward him.

The red planes were from the German air force’s notorious Jagdgeschwader 1—the Red Baron’s “Flying Circus,” an elite squadron whose pilots eschewed camouflage in favor of bright colors so that their enemies knew exactly who was coming at them. They were flying newly-delivered, ultra-maneuverable Fokker Dr.1 triplanes.

But the Germans weren’t the only ones with panache. Painted on the fuselage of the Bullard’s Spad S.VII was a red bleeding heart pierced with a knife, and the words tout le sang qui coule est rouge!—all blood runs red!

And ensconced in a box beside Bullard in the Spad’s cramped open cockpit was a monkey named Jimmy wearing a leather suit.

Bullard cranked his Spad around and dove toward the slower but more agile triplanes, his plane’s 150-horsepower Hispano-Suiza engine propelling the Spad beyond its 120 miles-per-hour maximum level-flight sped.

The triplanes swarmed towards the French fighters, twin Spandau machine guns winking. Tracers stitched the sky.

Banking hard, Bullard fell in behind one of the Fokkers, his single Vickers machine gun spitting rifle-caliber bullets synchronized to pass between the Spad’s spinning propeller blades. Pieces of fabric and wood tore off the weaving fighter. The Fokker turned back toward the German line, rapidly losing altitude.

Bullard closed in for the kill. But as he did so, bullets coming from below tore the wires in his fabric-covered wings. He had approached too close to German ground troops, who raked his plane with machine-gun fire.

Bullard fired one last burst into the Fokker, which belched smoke from its engine as it continued to descend. Bullard raced for the French side of the front line as his Spad, too, lost power. He barely succeeded in making a controlled landing on open ground close to the French trenches.

German gunfire continued ripping into his grounded plane, so Bullard hopped out with Jimmy tucked under one arm and hid in a shell hole for two hours. As night fell, French infantry sneaked forward and helped the Swallow and Jimmy make their escape—and even recovered his 1,100-pound Spad.

Back at the aerodrome, mechanics counted 96 bullet holes in the plane. French authorities couldn’t confirm the Fokker kill, but awarded Bullard a medal, anyway.

Although he flew for a French squadron, Bullard was an American. He would never officially fly in the service of his own country.

Because he was black.

Runaway boxer and Foreign Legionnaire

Eugene Bullard was born on Oct. 9, 1895 in Columbus, Georgia. His mother was of African and Creek Indian descent. His father was from Martinique.

Pervasive racial terrorism in the American South scarred the boy’s early life. Bullard in his memoirs wrote that, when he was eight, a mob nearly lynched his father for striking an abusive boss. Later, his brother Hector was lynched over a land dispute.

At the age of 12, Bullard sold his only goat for $1.50 and ran away from home, eventually becoming a horse jockey and joining a band of English gypsies. Around 1912 he stowed away on the German freighter Marte Russ.

The captain discovered Bullard and threatened to toss him overboard. Relenting, the skipper allowed the boy to work the ship for a while before depositing him in Aberdeen, Scotland.

Bullard moved on to Liverpool and began a profitable career as a professional boxer. He trained with welterweight “Dixie Kid” Aaron Lester Brown, another expatriate African American.

Bullard the boxer eventually departed on a pan-European tour with a slapstick troupe called the Freedman Pickaninnies. He won 42 bouts on the tour. In November 1913 he fought a match in Montmartre, Paris—and decided to stay there.

“It seemed to me that French democracy influenced the minds of both black and white Americans there and helped us all act like brothers,” Bullard wrote much later.

Racism prevailed in France, but social barriers in the European country were more permeable than was the “color line” in the United States.

At the outbreak of World War I, Bullard enlisted in the French Foreign Legion. He served in the third battalion of the 1st Marching Regiment of the 1st Moroccan Division. In the spring of 1915, his regiment deployed for the Second Battle of Artois Ridge, an attempt by the Allies to pinch off a German salient threatening supply lines between northern France and Paris.

Bullard’s unit assaulted the Souchez Heights, which dominated the surrounding terrain. Several weeks of fighting reduced his 250-strong company to just 54 soldiers, forcing the Foreign Legion to combine the second and third battalions of the regiment.

With the Great War devouring young lives at terrifying pace, the French army allowed colonial and Foreign Legion troops to integrate into metropolitan French army units.

Bullard in July 1915 transferred to the regular French army’s 170th Regiment of the 48th Infantry Division, the “Black Swallows of Death.” A 1972 biography gave Bullard the same nickname.

Bullard went onto lug machine guns in titanic battles at the Somme and Champagne in 1916. In the latter, his 500-man unit again was wiped out, leaving only 31 active personnel. Bullard escaped with a light head wound.

In February 1916 he marched to Verdun. German forces had launched an offensive to capture the heights around the city, intending to bleed dry the counterattacking French.

The ensuing 300-day battle was a slaughter. 700,000 soldiers were killed or wounded. The Germans suffered as much as the French did. “I thought I had seen fighting in other battles, but no one has ever seen anything like Verdun—not ever before or ever since,” Bullard wrote.

On March 5th, a shell exploded near Bullard, severely wounding him in the thigh as he was running a message for a French officer. Believing he was dead, Bullard’s colleagues tossed him on a pile of corpses.

He wasn’t dead. Bullard survived the wound and the battle and was awarded the Croix de Guerre for his bravery.

The Georgian spent the next eight months in a hospital in Lyons. His injuries disqualified him for further infantry service. While on leave, Bullard placed a $2,000 bet with a skeptical Mississippian named Jeff Dickson that he would become a combat pilot, instead.

Polish avant-garde painter Moise Kisling, a fellow former Legionnaire, underwrote Bullard’s flight training.

Bullard earned his French air force commission on Oct. 2, 1916. He initially trained as a gunner then transferred to the flight school at Chateauroux and Avord, where he piloted tubby, single-engine Caudron G-3 trainers and twin-engine G-4 bombers. Neither type could fly faster than 70 miles per hour.

On May 5, 1917 Bullard finally received his pilot’s license—and collected on his bet. This was no small feat. More pilots died in training than did in combat during World War I.

And combat was plenty deadly. In the war’s deadliest months, newly-inducted fighter pilots survived just 17.5 flying hours in combat, on average.

Bullard was one of roughly 200 American volunteer pilots serving in the French air force. But rather than serving with the all-American Lafayette Squadron, he was assigned to the French Escadrille N.93 based at Beauzee-sur-Aire, south of Verdun.

This made Bullard one of the first black fighter pilots. Contemporaries included Nigerian-Turk Ahmet Alik Celikten, who began flying in the Ottoman Empire’s air arm in 1916, Jamaican William Robinson Clarke, who piloted an RE.8 scout-bomber in action for the Royal Flying Corps starting May 1917 and Italian-Eritrean flier Domenico Mondelli.

Flying with the Lafayette Corps

The Georgian flew his first combat mission, a reconnaissance flight over German-occupied Metz, on Sept. 7, 1917 in a Nieuport 17 biplane fighter, a type noted for its maneuverability and fast climb rate.

On his second mission that day, his squadron bounced 16 Fokker triplanes escorting four bombers. In a swirling melee, the French fliers shot down the bombers and two triplanes at the cost of two of their own. Bullard noted that he fired 71 .303 rounds and came home with seven bullet holes in his own plane.

Six days later, Bullard transferred to Escadrille N.85 and began flying a Spad S.VII, a tougher and faster but less maneuverable plane than the Nieuport was. For good luck, he flew with his pet monkey Jimmy.

Bullard reportedly had won the monkey in a game of dice. Poor Jimmy succumbed to influenza before the end of the war.

Bullard flew 20 combat missions, claiming his second kill when he ambushed a V-formation of sturdy but underpowered Pfalz D.III fighters.

He missed his target on his first pass. The Pfalz’s pilot executed an Immelman turn, a half-loop-and-roll maneuver aimed at repositioning him behind Bullard’s plane. However, the American ducked his Spad into the clouds, only to reemerge below and to the right of his foe.

Again, there were no witnesses to confirm Bullard’s kill.

On Oct. 21, 1917 the first units of the American Expeditionary Force joined the war in Europe. Veteran combat pilots such as Bullard represented a precious resource for the new U.S. Army Air Service, which flew French-built Spad, Nieuport and Breguet biplanes.

Bullard applied to serve with the U.S. military and received a health inspection from Dr. Edmund Gros, the founder Lafayette Corps. Gros had opposed Bullard’s admission.

Despite criticism of his “enlarged” feet and tonsils, Bullard passed the check-up. But the Army refused him entry on the technicality that he couldn’t be commissioned as an officer, unlike his fellow Lafayette fliers.

Though 13 percent of the AEF was black, the U.S. military barred black personnel from vital roles. American officers likewise objected to the French military’s own, more relaxed attitude towards race.

The American Expeditionary Corps codified its racist sentiments in the infamous “Linard memo.” “Although a citizen of the United States, the black man is regarded by the white American as an inferior being with whom relations of business or service only are possible,” the memo explained.

French authorities should “prevent the rise of any pronounced degree of intimacy between French officers and black officers,” the memo continued, because “we cannot deal with them on the same plane as with the white American officers without deeply wounding the latter.”

Some time in 1917 Bullard got into a scuffle with a racist French officer at an inn. A few days later, Bullard was summarily discharged from French flying service over the reportedly minor incident, likely at Gros’s instigation.

An alternate account claims that Bullard actually punched the officer, though this version dubiously claims Gros was too enlightened from his time in France to harbor racist sentiments.

Undaunted, Bullard returned to service with the 170th Infantry Regiment, and served two more years before demobilizing in Oct. 24, 1919.

Bullard’s aggressive challenging of pervasive racist harassment would define much of his life. A decade later in 1928, Gros arranged for a monument honoring all the fliers in the Lafayette Corps—except Bullard.

Bullard and his flight mates protested. Rather than include Bullard’s name, Gros instead put up only the names of the 66 Lafayette pilots who died during the war.

The Paris years

Bullard remained in France after the war, and soon became a major figure in the booming “Lost Generation” of American expatriates in 1920s Paris.

After fighting Egyptian boxing champion Haig Assadourian to a draw in Cairo, Bullard launched a career as a jazz drummer at Joe Zelli nightclub in Paris’s Pigalle red-light district. Ernest Hemingway included Bullard as a minor character in his novel The Sun Also Rises.

In 1923, Bullard married Marcelle de Straumman, a white Frenchwoman from a wealth family in Franco-German Alsace. Bullard and Marcelle had two daughters, Jaqueline and Lolita, and a young boy who tragically died from pneumonia.

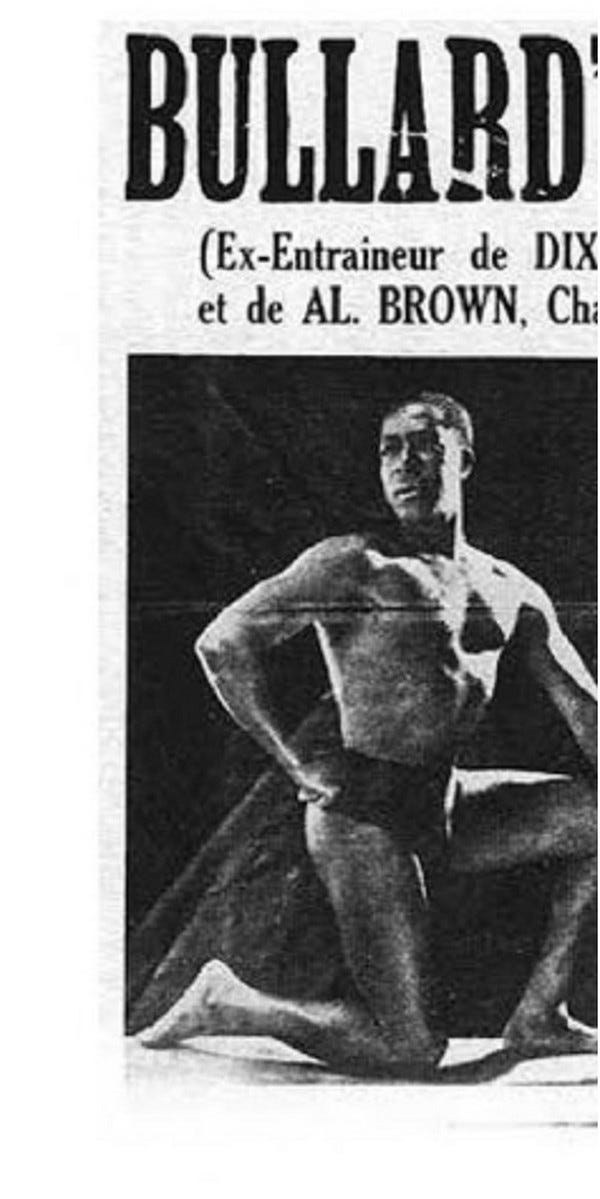

After a honeymooning in the coastal resort of Biarritz, Bullard bought the Paris jazz club Le Grand Duc, then opened a second club called L’Escadrille—“The Squadron”—at 5 Pierre Fontaine Street in Pigalle as well as a gym called Bullard’s Athletic Club. He became a grandfatherly figure in the booming cultural scene, which attracted many African-American expatriates.

The ex-fighter pilot palled around with trumpeter Louis Armstrong, invited dancer Josephine Baker to babysit his kids and hired Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes to wash dishes at his cabaret.

However, Bullard’s boisterous night-time living eventually alienated him from his wife, who wished he would retire to family life in the countryside. They divorced in 1935, with Bullard retaining custody of his daughters.

Some time before 1939, French counterintelligence operative George Lepanquais recruited Bullard to spy on German agents frequenting L’Escadrille. He was helped by 27-year-old Alsatian agent Kitty Terrier, code name “Cleopatre,” a woman whose father the Germans had killed in World War I.

“Of course, they figured no Negro could be bright enough to understand any language except his own,” Bullard wrote of the Germans. “So as the Nazis talked together at my tables and I served them, they were not at all careful about discussing military secrets within my hearing. These I promptly passed on to Kitty, who could slip unnoticed out of the bar, if need be, and pass along everything important to headquarters.”

The two put on such a convincing show of hosting German conspirators a Corsican gangster shot up L’Escadrille, believing Bullard to be a Nazi spy.

As Nazi troops poured into France in June 1940, Bullard put his teenage daughters under Terrier’s protection and evacuated them to the countryside. He then tried to re-enlist with his old French army unit, the 170th Regiment. But the fighting blocked his route out of Paris.

Fleeing with a column of shell-shocked refugees, he reunited with an old war-buddy named Bob Scanlon at the railway station at Chartres. Moments later, a Stuka dive-bomber plunged toward the station. Scanlon ducked for cover in a nearby crater. The Stuka’s bomb landed right on top of him.

The former aviator finally linked up with the French 51st Infantry Regiment, under the command of Maj. Roger Bader, who as a lieutenant in World War I had commanded Bullard’s platoon. On June 15, Bullard marched into battle lugging a 20-pound FM24/29 light machine gun.

“Major Bader assigned me to a machine gun company and ordered me to install machine guns on the left bank of the Loire River opposite the German infantry on the right bank and to take charge of a section,” Bullard wrote.

“We managed to hold the Germans back until midnight. Then they brought their artillery to within three miles of the city on the right bank. French resistance became non-existent and we were ordered to retreat. The Germans bombarded Orleans and set it on fire.”

Three days later, Bullard was scurrying across a street in Le Blanc when a shell slammed into his unit, killing 11 of his companions and wounding 16. Bullard was flung into a wall, injuring his spine. Shrapnel scorched his right brow.

Bader advised him to avoid capture at any cost. Hitchhiking, limping with a rifle as a crutch and riding a bike, he traveled 150 miles southwest to Bordeaux and finally evacuated across Spain to Lisbon, Portugal.

That July Bullard shipped back to the country he had left behind nearly three decades earlier. Settling in New York City, he received treatment at a French military hospital. Working with the U.S. ambassador to France, he arranged for his daughters to join him a year later.

Defiant to the end

Bullard determinedly participated in veterans groups and promoted U.S. intervention on the behalf of France. He ran into a solid wall of racism. Bullard got threatening letters warning him not to attend a veterans’ dinner. A man punched him in the eye when he refused to relinquish a bus seat.

He held a series of odd jobs. Security guard. Longshoreman. Perfume salesman. He briefly served as a interpreter of French for Louis Armstrong. After World War II, Bullard returned to Paris and found his club in ruins. He used French government compensation to buy himself an apartment in Harlem.

On Sept. 4, 1949, Bullard traveled to Peekskill, New York to attend a concert by Paul Robeson, a famous actor and civil-rights and union activist with Communist sympathies.

After the concert, a white mob organized by members of the American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars attacked the departing concertgoers, injuring 140 of them. Police stood by and watched, or even joined the rioters.

Film and photos of the incident depicted police knocking the 54-year-old Bullard to the ground. In a congressional hearing on the incident, John Rankin, a Mississippi representative, said the American people had no sympathy for the “nigger Communist and that bunch of reds who went up there.”

Bullard spent his final years living alone, working full time as an elevator operator at the Rockefeller building and slowly getting sicker and sicker.

Though largely unknown in the country of his birth, he was not forgotten by the one he had fought for. In 1954 the government of France invited him to ceremonially light the flame at the Tomb of the Unknown soldier at the base of the Arche de Triomphe.

Five years later, French president Charles de Gaulle appointed him a Knight of the Legion of Honor, France’s highest order of merit. That year Bullard began writing a personal memoir that two journalists in 1972 published as The Black Swallow of Death.

Historians have found inconsistencies in the book.

Bullard died of stomach cancer on Oct. 12, 1961. He was buried in uniform and with military honors in Flushing Cemetery in Queens.

In 1994 at the request of Gen. Colin Powell, the U.S. Air Force commissioned Eugene Bullard as a second lieutenant.

Sources

The Black Swallow of Death, based on private memoir by Eugene Bullard, adapted in 1972 by journalists P.J. Carisella and James W. Ryan

Eugene Bullard: World’s First Black Fighter Pilot by Larry W. Greenly

Eugene Bullard, Black Expatriate in Jazz-Age Paris by Craig Lloyd