Highway of Death at the Battle of Armageddon

Aerial slaughter by World War I biplanes changed warfare forever

by SEBASTIEN ROBLIN

On the evening of Feb. 25, 1991, Iraqi soldiers and civilian workers fleeing American armored divisions began streaming down Kuwait’s Highway 80, heading for the Iraqi border.

U.S. Navy planes spotted the miles-long traffic jam of trucks, buses, armored personnel carriers and tanks. The Americans destroyed the vehicles in front and in back, trapping the survivors between two heaps of fiery wreckage.

For 10 hours, jets swooped down, raining cluster bombs, Maverick missiles and cannons shells. Photographer Kenneth Jarecke snapped a photo of the carbonized remains of an Iraqi driver that was so graphic that magazines refused to publish it.

The carnage on the Highway of Death underscored a chilling truth. No target is more vulnerable to air attack then an army retreating in a dense column.

That was equally true in 1918, when Allied forces trapped their enemies on the original Highway of Death near the town of Megiddo in what is now Israel.

Megiddo is better known by its Greek name. Armageddon.

The Great War in the Middle East

During World War I, British forces battled Turkish and German troops for control of the ailing Ottoman Empire’s Middle East territories and their valuable oil fields.

Amid back-and-forth fighting, the British convinced nationalistic Arabs, Jews and other ethnic groups that their interests lay in revolting against Ottoman rule.

In early 1918, British general Edmund Allenby was poised to go on the offensive in Palestine. But that spring, he had to relinquish 60,000 troops for the fighting in Europe. He eventually compensated with fresh infantry and cavalry divisions from India.

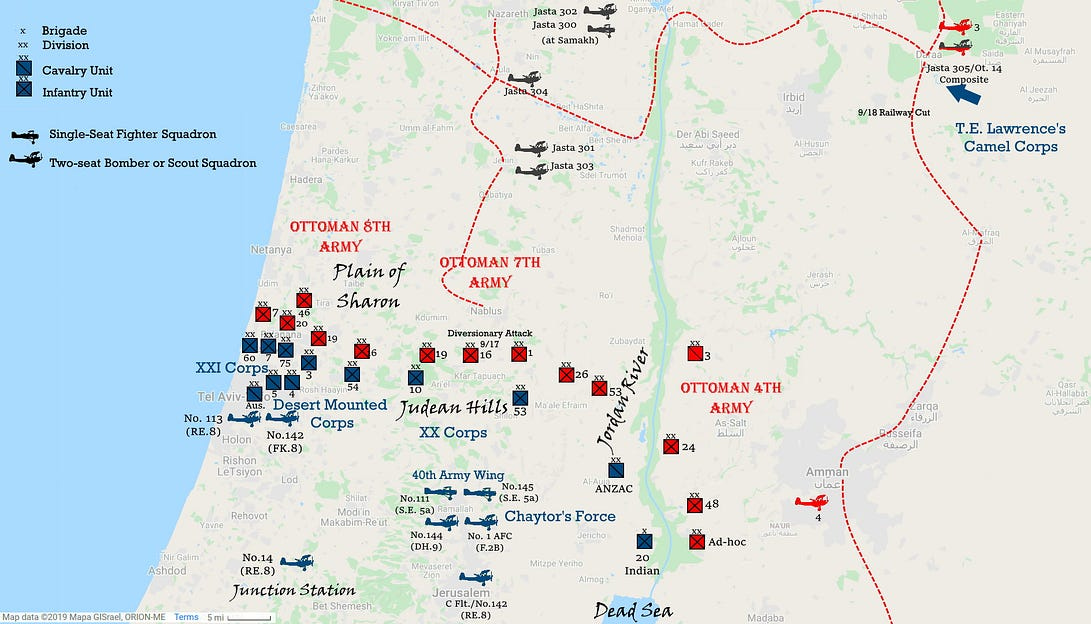

The three armies of the Ottoman Yildrim Army Group, facing Allenby in Palestine, were also in rough shape. German general Otto Liman von Sanders spread all his troops across a 56-mile front line stretching from El Tire on the Mediterranean coast to Amman, Jordan—leaving virtually no mobile formations in reserve.

The armies were supplied via the Hejaz railway, itself guarded by string of outposts.

Altogether, Sanders mustered 40,600 infantry, 969 light and heavy machine guns and 402 artillery pieces. The Ottoman 8th Army, headquartered at Tulkarmm, held the Mediterranean coastal plain of Sharon with five infantry and one cavalry divisions and an ad-hoc German regiment.

In the center, the 8th Army based at Nablus defended the Judean Hills with four infantry divisions and another German regiment.

Finally, the 4th Army, based at Es Salt, defended key cities east of the Jordan River, such as Amman, with four infantry and one cavalry divisions.

By the fall of 1918, Allenby altogether commanded 52,000 infantry, 12,000 cavalry and 579 field guns. They were not enough for a direct assault on the entrenched Ottomans. Instead, Allenby envisioned a battle of maneuver.

Redeploying troops clandestinely at night, he massed five infantry divisions, a French and Armenian brigade and 23 artillery batteries on the western coast, building up an overwhelming local superiority on an eight-mile stretch of the front line.

These were to open a breach through which the Desert Mounted Corps—an Australian and two Indian cavalry divisions—would plunge through, racing northeast toward Afule and Nazaret to cut off the Ottoman 7th and 8th Army’s only line of retreat.

Prior to the main assault, the smaller XXI Corps (two divisions) and Chaytor’s Force (an ANZAC cavalry division plus a mixed Indian-Jewish infantry brigade) would launch small-scale diversionary attacks against the Ottoman 8th and 4th Armies, while Arab riders led by Col. T. E. Lawrence—“Lawrence of Arabia”—would raise chaos behind Ottoman lines.

Air war over the Middle East

But Allenby’s plan only worked if his counterpart remained ignorant of the actual disposition of his troops. And that meant he needed control of the air.

Aircraft had already proven decisive in earlier battles over the vast, open expanses of the Arabian peninsula. Airplanes could track the movements of enemy armies, strafe exposed columns and deliver critical messages, personnel and supplies to remote outposts and wayward units.

The Royal Air Force, then only five months old, was formed by combining the former Royal Flying Corps and Royal Naval Air Service. The RAF Palestine Brigade counted 105 aircraft in two wings.

The three squadrons of №5 Air Wing operating from bases in Sarona (the future Tel Aviv), Jerusalem and Junction Station, each providing direct support to a different corps.

№113 and №142 squadrons flew notoriously temperamental, two-seat R.E.8 scout bombers out of Sarona and Junction Station, while №124 squadron flew slower but more forgiving Armstrong-Whitworth F.K.8s out of Jerusaelm and Sarona.

Like most two-seater observation planes in World War I, these mounted a single forward-firing machine gun above the wing and a ring-mounted Lewis machine gun operated by the observer and could carry around 200 pounds of bombs.

The 40th Army Wing, based at Ramallah, undertook broader strategic reconnaissance, strike, interdiction and air superiority roles. It included two squadrons of speedy S.E. 5a fighters (№111 and №145), a squadron of heavier two-seat Airco DH.9 bombers capable of lugging 460-pound bombloads and finally №1 Squadron of Australian Flying Corps.

The Aussies mostly flew the Bristol F.2B, an unusually agile, two-seat scout fighter that was fast and robust enough to make an effective fighter and bomber. The Bristol Fighter could carry up to 240 pounds of small bombs. Some even carried a then-rare aviation technology, a trailing wireless radio transmitter for reporting sightings of enemy forces.

By 1918, the three Ottoman army aviation squadrons (3rd, 4th and 14th) in Palestine been reinforced with the remnants of six German squadrons that transferred in 1916 and 1917 (Jasta 300 through 305). Both primarily flew two-seat AEG C. IV observation planes as well as older Rumpler C.1s and Albatross C.IIIs.

German Fliegerabteilung 300 also received 15 Albatross D.III and D.V fighters with twin, forward-firing machine guns and a second wing-mounted radiator to cope with the desert heat. While capable in 1917, they could not keep up with British S.E.5s in 1918.

By September, two squadrons at Sama supported the 8th Army. Three squadrons based at Jenin and Afule covered the 7th Army. Three squadrons at Deraa and Amman assisted the 4th Army.

For Allenby’s gambit to succeed, it was vital to deny German and Ottoman fliers the chance to spy on his troop dispositions. Fortunately, he had the means to do so. Two squadrons of S.E.5a biplanes, each equipped with two forward-firing machine guns and boasting a then-unsurpassed maximum speed of 138 miles per hour.

In the weeks leading up to Allenby’s offensive, the S.E.5a planes maintained around-the-clock patrols over Ottoman air bases in Jenin and Daraa, shooting up anything that moved on the ground or in the air and raining propaganda leaflets on demoralized Ottoman troops.

The campaign was successful: Ottoman air incursions decreased from 100 in June to just 18 by August.

Diversionary moves

Three days ahead of the main attack on Sept. 16, Col. T. E. Lawrence flanked the Ottoman lines from the east with the 400 Arab riders of the Hejaz Camel Corps supplemented by a French Algerian mountain artillery battery, an Indian machine gun company, Australian armored cars and two British-piloted B.E.12 observation planes.

Lawrence’s mission was to cut off the vital Hejaz railway intersection near Deraa, Syria, which was also the site of a key German air base. DH.9s from №144 squadron dropped 2,500 pounds of bombs on the base.

But the German fliers weren’t out of the picture. Australian fighters shot down a German plane from Derra later that day. Then on Sept. 18, German warplanes strafed Lawrence’s forward camp at El Umtaiye, shooting down one of his B.E.12s and destroying the other with bombs.

By Sept. 18, Lawrence’s riders had captured Tel Arrar station and demolished the railway with explosive charges. His activities attracted two or three thousand more Arab tribal warriors to join him. XX Corps also began diversionary attack on the 7th Army in order to lure Ottoman reinforcements in the wrong direction.

But on the eve of Allenby’s main stroke, his deception nearly unraveled when an Indian deserter warned the Ottoman 8th Army of the impending onslaught. Fearing the deserter to be another ploy from Allenby, Sanders insisted his troop maintain their positions.

At 1:15 in the morning on Sept. 19, a huge twin-engine biplane soared through night sky toward Afule. At the controls was Australian pilot Ross MachPherson Smith, with three comrades manning defensive machine guns.

Three weeks earlier, №1 Squadron had received a single Handley-Page O/400—then one of the largest airplanes in the world. The boxy heavy bomber could fly eight hours on internal fuel or carry a ton of bombs over a shorter distance.

With remarkable precision, Smith destroyed the telephone exchange at Afule and disabled the railway yards for a good measure using 16 112-pound bombs.

Five hours later, DH.9 bombers knocked out another telephone exchange at Nablus.

Together, the raids entirely cut communications between the 4th Ottoman Army on the east side of the Jordan River and the two armies to the west.

At 4:15 in the morning, 385 British guns fired across the positions of the 8th Army on the coastal Plain of Sharon. Rather than frittering away ammunition and the advantage of surprise on a lengthy bombardment, Allenby promptly launched the infantry of XXI Corps.

At the same moment, R.E.8s from 113 Squadron dove toward the battered Ottoman positions and dropped 60 field-improvised pyrotechnic devices, creating a 400-yard-long smokescreen masking the advancing infantry.

In just two hours, Allenby’s infantry overran the Turkish entrenchments and their thin layers of barbed wire. The 94 mounted squadrons of the 4th and 5th Cavalry Divisions poured through the breach, accompanied by two batteries and two patrols of armored cars.

The 113 Squadron history describes the cooperation between aircraft and cavalry. “One of the aircraft from 113 Squadron noticed a house and an orchard a short way ahead of the leading elements of the cavalry. Flying low over the area the pilot and his observer discovered that the orchard was occupied by Turkish troops and transport.”

“A note was written and dropped to the approaching elements of the cavalry. They put in a quick attack, taking the Turks by surprise. Sixty prisoners were captured with two guns and 12 wagons at a cost of one life and two men wounded.”

By noon, reconnaissance flights revealed that the entire Turkish 8th Army was in full retreat. British DH-9 and S.E.5 biplanes immediately harried them. Five Australian Bristol fighters swooped down on one column, peppering it with small bombs. Turkish machine-gun fire caused two of the aircraft to make forced landings. Indian cavalry rescued the downed pilots.

That evening the Handley-Page struck again, this time blasting the airfield and railway at Jenin. Allenby’s cavalry now began advancing at a pace that would average 20 to 30 miles a day. Reconnaissance flights the following morning revealed 8th Army positions had evaporated, with Turkish troops pouring out of Jenin and Nablus.

At dawn, Bristol Fighters from №1 Squadron pounced upon a five-mile-long column consisting of 200 trucks edging between a rock wall and the edge of a steep precipice, as described in The Australian Flying Corps in the Western and Eastern Theatres of War by Frederick Morley Cutlack.

“They had only eight bombs, but three of them made direct hits on transport and blocked the road, and the effect of the others was equally destructive. Frightened by the explosions, and by bursts of machine-gun fire delivered from close overhead, many horses bolted over the precipice on one side of the road and, on the other, men ran in panic to shelter in the hillside. Several motor-lorries, either deserted by their drivers while still running, or colliding with bolting horse- transport, likewise fell over the precipice.”

A similar fate befell Ottoman forces fleeing Samaria for Afule at 9:00 in the morning. “Between Burka and Jenin five machines dropped 40 bombs and fired 4,000 machine-gun rounds into several retreating columns … They were closely packed, and nearly every bomb fell plumb among them. When the airmen had exhausted their ammunition, they returned to the aerodrome, filled up again, and repeated the attack at noon in the vicinity of the village of Arrabe.”

“Not a man or a beast in this road escaped; those who survived the air attack and finished their march, delivered themselves up gratefully to the light horse in the hills on the southern fringe of the plain of Armageddon.”

Ironically, the 20th Deccan Cavalry had already captured Afule and its valuable airbase and railway at 7:15 that morning with support from three armored cars. The Handley-Page O/400 soon began flying down gas and spare parts to the newly secured air base.

A single German observation plane carrying bags of mail landed there after its capture. Belatedly realizing the situation, the pilot immediately tried to take back off but was injured by machine-gun fire from armored cars and captured.

Another cavalry brigade nearly overran the Yildrim Army Group headquarters in Nazareth. General von Sanders barely escaped in his staff car while most of his office staff fell in a last stand battling Indian cavalry.

Highway of Death

At sunrise at 6:00 on the morning of Sept. 21, two Australian Bristol Fighters patrolling over the Wadi Fara beheld a remarkable site. More than 600 wagons from the 7th Army streaming northward in a six-mile-long convoy also including infantry, cavalry and motor transport.

The squadron-leader used his radio to transmit the news to the rest of the squadron. The RAF rapidly organized a deadly relay of death. Every three minutes, a two-ship element would swoop down on the column, machine guns rattling. And every half an hour, a six-ship flight would plaster the fleeing Ottomans with a heavier attack.

Over the course of the day, seven British and Australian squadrons unleashed 56,000 machine-guns rounds and nine tons of bombs on the retreating column as it struggled to thread its way through a narrow, s-shape valley.

“The panic and the slaughter beggared all description,” Cutlack wrote. “The long, winding, hopeless column of traffic was so broken and wrecked, so utterly unable to escape from the barriers of hill and precipice, that the bombing machines gave up all attempt to estimate the losses under the attack, and were sickened of the slaughter.”

“The passes were completely blocked ahead and behind by overturned motor-lorries and horse-wagons; men deserted their vehicles in a wild scramble to seek cover; many were dragged by the maddened animals over the side of the precipice. Those who were able cut horses from the wagons and rode in panic down the road to Damieh.”

ANZAC historian Charles Guy Powles recalled seeing the aftermath from the ground. “Dead men and animals, torn about with ruthless bombs, swollen and distorted, stank fearfully. Many of the animals still lived in speechless agony, and some of the wretched wounded were in many cases pinned down by carrion, but there was no time to stop and help them.”

“That was for others who came behind. War is Hell, and looks well only in a picture show.”

Ground troops later counted the abandoned wrecks of 59 motor vehicles, 87 field guns and more than 800 wagons on that stretch of highway. The RAF lost two aircraft and their crews to ground fire.

By the end of the attack the day the 8th Army ceased to exist. “The RAF lost four killed,” Lawrence wrote. “The Turks lost a corps.”

But the extent of the slaughter upset even the victors. The commander of XXI Corps accused an RAF general of being a “butcher.” The 113 Squadron history notes the “sickening slaughter … deeply affected the airmen.”

To the north, Ross Smith flew Lawrence of Arabia in the backseat of his Bristol Fighter to rejoin Arab riders at Um-es-Surab on Sept. 22, bearing news of the victories down south. Two more F.2s accompanied him.

The Handley-Page followed the next day, loaded down with supplies. The sight of monstrous bomber “moved the Arab tribesmen to the wildest enthusiasm.”

The crews of the three Bristol Fighters were breakfasting the morning of Sep. 23 when they spotted three German aircraft approaching. The Aussie pilots scrambled into the air and gave pursuit, shooting down a scout plane and destroying the other after it landed at Mafrak. The pilots returned to base to finish their porridge.

But then a second trio of German scout planes came soaring at them from Deraa, resulting in a bizarre engagement, as described by Cutlack. “Ross Smith and Mustard again flew out and drove down all three. Two landed near the railway and ran along the ground to Turkish outposts; the third returned hurriedly to Deraa. The Australians, after the chase to Deraa, visited the other two machines and fired 50 rounds into each on the ground at close quarters.”

A seventh German plane managed to bomb Um-es-Surab that afternoon, only to be chased all the way back to its aerodrome by a Bristol. As it landed, the Bristol’s back-seater destroyed the aircraft and killed both crew with his Lewis machine gun.

For good measure, №1 squadron aircraft based at Ramallah struck the Deraa airfield the morning of Sept. 24, destroying a hangar and three more two-seaters on the ground, bringing an end to Ottoman air opposition.

Lacking communication lines, it was not until Sept. 22 that the Ottoman Fourth Army realized that its two sister formations no longer existed. Meanwhile, diversionary attacks by Chaytor’s Force pressed the army.

Lest it meet the same fate as the 7th Army, the 4th too began a hasty retreat. Australian fighters strafed the retreating soldiers at Suwail. Chaytor’s Force advanced at their heels, snapping up Es Salt on Sept. 23.

At 7:00 that morning, №1 Squadron swooped down on a column fleeing Es Salt for Amman, plastering the orderly convoy with 48 bombs. “Eight direct hits on wagons or lorries achieved the purpose,” Cutlack wrote. “Men fled into wadis for cover; under a withering fire of 7,000 machine-gun rounds every man and beast who could leave the road did so. Thereafter the day’s air attacks were directed upon Amman, where traffic was converging from all quarters.”

By Sept. 26, Chaytor’s Force had captured Amman and Allenby’s troops collectively had taken 50,000 prisoners. Of the Yildrim Army Group, only the battered remnants of the 4th Army remained.

Four days later, Indian cavalry descended upon the grand prize. Damascus. The Australian pilots again spotted a column of bedraggled Ottoman soldiers fleeing the city.

“Maughan dived at them, but the Turks remained sitting resignedly on the ground, too exhausted to move,” the Australian history recorded. “They had run to a finish. The Australians, in pity, abstained from firing on them.”

Allenby’s wildly successful offensive prompted a Turkish armistice a month later on Oct. 31, 1918, bringing an end to centuries of Ottoman rule. They carved the former Ottoman territory into countries which continue to define political divisions in the Middle East.

The Battle of Megiddo also foretold the decisive effects of fast-paced tactics combining air power, mobile ground forces and radio communications. Allenby’s war planes not only inflicted heavy casualties and broke Turkish morale, they afforded him superior situational awareness of the position of enemy and friendly forces.

His emphasis on destroying Ottoman air power on the ground denied Sanders that same awareness.

In lieu of tanks and armored carriers, cavalry and armored cars proved capable of hamstringing vital lines of supply and communion, causing enemy formations to panic. Thus Allenby’s offensive foretold the mechanized warfare that would mark the remainder of the 20th century, from the German Blitzkrieg in Poland and France to the 1967 Six Day War.

And the 1991 Gulf War with its own Highway of Death.