In 1942, a British Desert Force Motored 2,000 Miles to Attack an Italian Airfield

The Long Range Desert Group battled sand, heat and the Axis

by CALEB LARSON

September 1942. North Africa. The British Army’s Long Range Desert Group was in Tunisia, traveling west toward the Mareth Line, a 28-mile stretch of defensive fortifications stretching roughly northeast to southwest from the Mediterranean Sea into vast desert.

Built in 1936 by the French colonial administration to defend against an expected attack on French Tunisia by Italy in the event of war, the terminus of the Mareth Line was engulfed by an imposing desert. French surveyors in the 1930s had deemed the southern desert impassable for large, slow-moving convoys of tanks and armor.

By 1943 the Mareth Line had fallen to Italy and was occupied by a mixed German-Italian force. Axis engineers had reinforced the Line with antitank and antipersonnel mines, miles of barbed wire, antitank trenches, antitank guns and more artillery.

It, in a word, was impassible.

The French had estimated that under favorable conditions, the troops manning the Mareth Line could hold out for two years. Little did the French surveyors know there existed a passage through the desert that outflanked the Mareth Line. The Tebaga Gap.

The Axis troops occupying the Mareth Line also did not know.

Three Chevrolet 30 CWT trucks roared loudly across the desert, low-pressure desert tires peeling through fine Tunisian sand. Standing upright in the bed of one of the trucks between wooden boxes stuffed with .303-caliber belts and cans of gasoline, an Englishman tightly held the fist grips and thumb triggers of twin Vickers K machine guns mounted above the cab, scanning for shapes on the horizon.

Using old French and Italian maps that were woefully incomplete, the British LRDG struck out into the desert. The patrol group was driving southwest, skirting the Matmata Hills that capped the end of the Mareth Line, looking for a pass that would allow columns of British armor and trucks to flank the Axis-held Mareth Line and updating their maps to better reflect the terrain.

It and other patrols had been probing the far reaches of the hills, trying to avoid being seen from the air by Axis air patrols and from the ground by tanks and armored cars. On most patrols, the heaviest guns the LRDG carried were American .50-caliber Brownings, which with a bit of luck could stop an armored car.

Tanks were best left alone. For ambushes, the patrols would include a weapons trucks that mounted 37-millimeter Bofors anti-tank guns or captured 20-millimeter Italian Breda antiaircraft guns. But this LRDG patrol was not a direct-action outfit. The LRDG avoided engaging the enemy when possible.

Its unofficial motto was Non Vi Sed Arte. “Not by Strength but Guile.”

The group attempted to hide in plain sight in the desert, avoiding Axis patrols, using sand dunes and camouflage netting to blend in with the landscape. This was its advantage. It was constantly outgunned and under-armored, but more maneuverable, usually faster and with a full load of gasoline and access to hidden fuel dumps in the desert, could travel much farther than armored cars and tanks could do.

The real killers were the six- and eight-wheel armored cars. Sporting 20-, 50-, or 75-millimeter guns, they came in various configurations but all were highly mobile. Due to their smaller stature, they more easily could hide behind sand dunes or rocky outcrops than could their heavily-armored counterparts.

As the patrol drove around rocky outcrops, its vehicles’ engines strained under their heavy load of ammunition, fuel, water, food, spare parts and men. They were a mixed collection of Chevrolet 30 CWT trucks, Fords and later some Willy’s Jeeps from the United States.

Under normal conditions these trucks were rather reliable, but the heat and rough terrain made anything mechanical prone to breakdowns. Stopping for repairs happened all too often. This close to the enemy delay could be fatal.

A Captain Wilder, commanding the lead truck, carefully drove around a bend in the dusty road, followed by two other Chevys on patrol. His driver yelled, slammed the brakes. The brake drums had nearly no pads left, and the truck screeched to a halt. Simultaneously, a rocky ledge exploded, showering the patrol in bits of shell and limestone, souvenirs from the ancient seabed beneath them.

“Reverse! Pull out! Move!” Wilder yelled, his voice cracking. An eight-wheel German Sd. Kfz. 234 had been lying in wait a few hundred yards out, its crew hoping for a patrol to drive by.

Miraculously, the German gunner had aimed high and missed. The three trucks were in a bottleneck, however. The front two trucks could only reverse out to safety once the tail truck was out of the way.

Wilder didn’t hesitate. He commanded the gunner manning twin Vickers Ks to pepper the car with .303 rounds. They couldn’t penetrate, but perhaps they could puncture a tire, find their way into a vision slit or at least cause some confusion.

Anyway, they didn’t have anything heavier. Wilder regretted not putting the truck with the .50 Browning in front. With some armor-piercing rounds, they’d stand a better chance.

Wilder’s truck shifted from first to second, crunching gears. The truck behind his lit up the German car. Evidently everyone inside the German vehicle had been caught off guard, as the second shell from their 75 was slow to come.

Again, high. The North African campaign had been hard on both sides, and replacements had entered into service without adequate training. Wilder thanked his lucky stars.

Inception

The Long Range Desert Group, or LRDG for short, was a motley crew. Founded in 1940 by the English explorer and geologist Ralph Alger Bagnold, the LRDG initially recruited farmers and ranchers from New Zealand, who were, as the thinking went, tough and hardy enough to thrive in the harsh desert climate.

As the LRDG grew, the recruitment pool expanded to include Southern Rhodesians, Australians and others. There were several all-Indian patrols, although they were segregated from the others. The LRDG never numbered more than 350 people.

Driving in the deserts and badlands of North Africa is much like sailing a ship. Cut off from supplies, travelers take with them everything they need. First and foremost water, then food. If traveling by motor vehicle, gasoline or diesel. If armed, ammunition. So traveled the Long Range Desert Group.

There’s a dearth of landmarks in the desert. And using a magnetic compass to find north proved to be problematic due to large mineral deposits that prevented accurate readings. The solution was the sun compass.

Bagnold was an early pioneer of using a sun compass to find true north. His iteration of the sun compass was essentially a brass disk mounted on the dash of the trucks. It was marked with degree points like a compass, but with a metal rod pointing vertically outward from the center of the disk.

It functioned much like a sundial, the shadow of the rod indicating the desired direction of travel, with periodic adjustments according to the time. The driver’s job was to “shoot the sun” by maintaining a steady heading and keeping the shadow of the rod in the same place on the sun disk. Not an easy job.

Bagnold had spent much of his pre-war time in North Africa, exploring the vast expanse by car. A trained geologist, he gained invaluable experience motoring around the desert and developed techniques for driving over massive dunes and loose sand.

Equally as dangerous as the Axis armor the LRDG regularly encountered was heat. During the day, outdoor temperatures regularly exceeded 110 degrees Fahrenheit. Intense heat settled in the soles of feet and underarms and stayed there uncomfortably, indefinitely.

Libyan desert also was dry. It blistered lips, caused temporary sun-blindness, disintegrated rubber tires, cracked engine sumps, melted hoses and made gaskets combust. Any exposed metal surface quickly became untouchable, so anything that was to be handled was either covered in canvas cloth, or the men wore thick leather gloves.

Ironically, the Libyan nights were also punishing in the opposite extreme. Night temperatures regularly dipped below 40 degrees Fahrenheit, not counting wind chill. The LRDG men would bundle up in winter caps and shaggy Hebron coats, thick goatskin coats they bought from the local Arab populace.

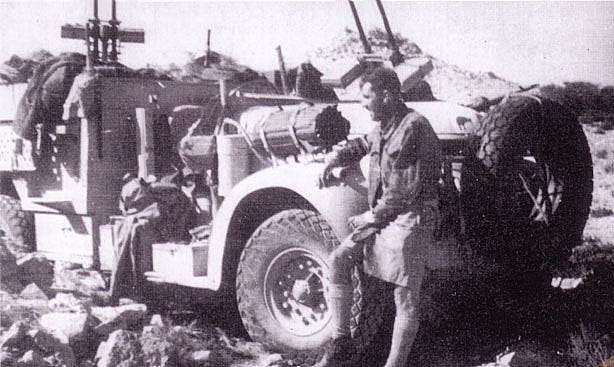

The LRDG tinkered with a wide variety of trucks. All had special modifications for the desert climate and terrain. Wide, low-pressure sand tires. Oversize condensers. Steel sand channels. Saving weight was at a premium, so the soldiers stripped off roofs, windshields, side mirrors, everything.

The LRDG experimented with several configurations of vehicles, but favored Chevy 30 CWTs and other rear-wheel drive trucks because of their lower weight and higher fuel-mileage compared to heavier, four-wheel-drive gas-guzzlers.

Pragmatic to the extreme, the crews would sometimes use a communal “honey pot” to relieve themselves. In case a radiator hose ruptured, they wouldn’t have to use precious water supplies to refill.

Operation Caravan

In the lead up to the Second Battle of El Alamein, Allied forces targeted Axis aircraft and fuel dumps.

Operation Caravan was one of four separate and simultaneous operations that together made up Operation Agreement. The LRDG was tasked with locating an Axis airfield near the town of Barce and causing “the maximum amount of damage and disturbance to the enemy.”

The LRDG would have to drive 1,100 miles for the outward journey alone. In order to avoid aggressive Axis ground patrols and observation from the air, the LRDG would cross the Great Sand Sea, a desert twice the size of Lebanon.

It was some of the worst terrain for a caravan to make a long-distance crossing. The Great Sand Sea is a fine powdery sand that offers little traction. Sharp jutting stones can tear tires like cardboard.

Two patrol groups were assigned to Operation Caravan. Patrol T1 commanded by Capt. N. P. Wilder, and Patrol G1 under Capt. J. A. L. Timson, both under the overall command of Maj. John Richard Easonsmith. Two heavy trucks hauling fuel followed the patrols.

The soldiers loaded the heavies with captured German “jerry” fuel cans that were much more robust than were the British “flimsies,” four-gallon tins that were so fragile you could poke holes in them with a pencil.

Reinforced with additional leaf springs, the heavies each could carry 3,300 pounds of fuel. They would top off G1 and T1 as long as they could then return to base. Another pair of heavies were at an outpost closer to the objective and would rendezvous with G1 and T1. Together the patrols mustered 17 vehicles and 47 souls.

Traversing sand dunes was more art than science. The convoy suffered setbacks almost immediately after setting out. In order to mount the steep dunes, one had to hit the gas in the troughs between and maintain a steady speed toward the top.

While crossing a dune, one of the Jeeps crested too quickly. The Jeep buried its grill in the sand on the opposite side, flipping end over end. It landed on top of both the gunner and his driver, severely injuring them. T1’s comms truck radioed for help and both men evacuated by air. T1 was down a pair of .303-caliber Vickers K machine guns, a gunner, a driver and a Jeep.

After 11 days and many breakdowns and repairs, G1 and T1 arrived outside their objective. An Italian garrison and airstrip in Barce.

Easonsmith decided that G1 would first create a diversion by attacking the Italian barracks and infrastructure. Meanwhile T1, which had one heavy equipped with a captured Italian 20-millimete Breda would lie in wait outside the airfield. The Breda would fire toward the airfield, covering the patrols’ retreat.

But the LRDG had been compromised. An Italian scout plane had seen the patrols and alerted the garrison at Barce. Worse, the Breda-carrying heavy from T1 crashed into the truck ahead of it in the scramble to get into position, destroying its radiator.

It was no longer driveable. T1’s heavy firepower was gone.

The assault

T1 barreled down the main road leading to the airfield. The patrol was not immediately challenged by the sentries on the road. So many British and captured American tanks and trucks were in use by Axis troops that it was not immediately clear T1 was hostile.

Several Italian sentries peered down the road at the trucks coming toward them, nervously fingering their rifles. Under normal circumstance, the LRDG would wear Italian or German caps and give a Roman salute when passing Axis troops. Lots of unpleasant situations had been avoided this way.

Today was not one of those days.

Wilder was driving point. He glanced to his left, nodding at his gunner in the passenger seat. The gunner pointed his license-built Browning down the road and pulled the trigger. The .303 rounds found their marks.

Wilder pressed the gas pedal, enjoying driving on the hard gravel road after 11 days of torturous desert crossing. The airfield grew larger as they approached. The airfield gates were shut but, incredibly, not locked. Wilder shoved the double doors inward and open.

Back in Wilder’s truck, the gunner looked back at the line of British trucks idling on the road waiting to drive onto the airfield. Without the the Breda providing overwatch, T1 had adjusted its plan. The trucks would drive inside, firing at the aircraft and buildings while several groups of men on foot ran from plane to plane, attaching Nobel 808—an early plastic explosive—to the engines or gas tanks.

Wilder and the others poured inside. One of the patrol trucks pulled in front of a low brick blockhouse. The gunner racked his .50-caliber Browning and two other soldiers jumped out.

The two ran toward the blockhouse and hit the wall on both sides of one of the windows. The man on the left broke the glass with the butt of his rifle while the other tossed two Mills bombs inside. Both scampered clear of the building as a the grenades exploded, blowing the wooden door outward.

Two Italians stumbled out and were gunned down by the waiting gunner. “Christ,” Wilder muttered to himself as he speeded to the far end of the airfield and a group of parked Cant Z. 1007 Alciones. These three-engine medium bombers were highly capable but had a serious flaw. Most of the airframe was wood and burned like kindling when hit with tracer fire.

Wilder glanced from his seat at the other trucks that had dispersed around the airfield. Groups of LRDG men, small in the distance, had dismounted and were sprinting toward parked aircraft. The lead men loped from engine to engine, attaching clean white bricks of Nobel 808. The men behind them inserted and set off fuses.

Sharp primary explosions from the Nobel 808 cracked across the tarmac. The sun set, reducing visibility. One of the LRDG crews found the airfield fuel dump and set it alight with tracer fire. A deep booming explosion ripped the air. Burning fuel lit the airfield in an orange glow.

One of T1’s Jeeps pulled up next to Wilder. “No more 808, sir,” yelled a trooper through the noise. Wilder scanned the airfield. Perfect time to make tracks, he thought to himself. “Pack it up and move it out!”

Aftermath

Operation Caravan was a success. According to official British reports, 32 Italian aircraft were damaged or destroyed. Italian reports indicated 16 aircraft destroyed.

While T1 hadn’t lost any men during the assault on the airfield, the journey back to British lines was decidedly more perilous. Several trucks had to be written off after attacks by Axis planes. There were casualties.

Operation Caravan was the only successful component of Operation Agreement, which overall was a disaster. The Second Battle of El Alemein, a month later, marked a turning point in the North Africa campaign. The Axis in the region surrendered the next year.

Wilder and Easonsmith were awarded the Distinguished Service Order for their leadership during Operation Caravan. Three LRDG men were awarded the Military Medal for bravery in battle, and one received the Military Cross in recognition for gallantry.

After the surrender of Axis forces in North Africa in 1943, the LRDG transferred to Greece, were it fought on foot in the hills and mountains. During the Battle of Leros, Easonsmith was shot and killed by a sniper.

Bagnold’s 1941 book The Physics of Blown Sand and Desert Dunes eventually found its way to NASA, which applied it to the study of dunes and erosion on Mars. The agency named the Bagnold Dune Field on Mars after the desert-group founder.

After V-E Day, the LRDG petitioned to be sent to Asia to fight the Japanese. Instead, the British Army disbanded the group.

In the early 1980s someone found one of the LRDG’s abandoned Chevy trucks in Libya and donated it to the Imperial War Museum in London. It’s on display in the condition in which it was discovered.