Second Stringers

A flashback to Iraq in 2005, and a surge of part-time soldiers into an unforgiving war zone

Between February 2005 and March 2006, I traveled to Iraq several times for The Village Voice—the New York City alternative newspaper that folded in 2017 and now reappears only sporadically. I wrote 16 stories for The Village Voice. The paper paid me $1,000 for each, essentially launching my writing career.

My second story for The Village Voice appeared in March 2005, and asked a lot of hard questions of a lot of under-prepared American reservists. I’ve reprinted it below.

It’s not hard to imagine what the soldiers of the 272nd Chemical Company, a unit of the New York National Guard’s 42nd Infantry Div., were thinking when they spotted the vehicle barreling towards them through the falling darkness.

Strewn out on the highway near this Sunni city on Jan. 29, 2005, their own vehicles idling as they effected quick repairs to a malfunctioning truck, the company’s soldiers were probably imagining the horror stories they’d heard in recent weeks while training in Kuwait for their yearlong deployment to the Sunni triangle—stories about drug-addled jihadists in automobiles packed with explosives.

Just three days earlier, a foreign bomber in a compact car blew himself up alongside some Iraqi policemen in downtown Baqubah, wounding several people and scattering pieces of himself all over a city block.

To the inexperienced Guardsmen of the 272nd—a unit that, before now, had never been to war in its 25-year history—the vehicle drawing every closer to their vulnerable convoy could very well contain a 72-virgins-crazed suicidal terrorist heaven-bent on blowing himself up and taking some foreign infidels with him.

The driver of one of the outermost idling trucks flashed his lights as a warning to the approaching vehicle.

It kept coming.

A soldier manning a truck-mounted .50-caliber machine gun—a weapon powerful enough to shoot down aircraft—opened fire. And several Iraqi Army officers inside the vehicle were pierced by shattered glass and thumb-sized metal slugs.

One died instantly. At least two more were badly injured. Their vehicle came to a halt.

Soon, the soldiers of the 272nd realized what they’d done. They’d killed an ally.

Wonks call it friendly fire. Military historians call it fratricide. To military planners, it’s a nagging problem in a country where friend and foe are nearly indistinguishable.

Just ask Giuliana Sgrena, the Italian journalist briefly kidnapped in Baghdad in February. On March 4, Sgrena was wounded when American soldiers manning a checkpoint near Baghdad International Airport opened fire on a compact car carrying her and Italian intelligence agent Nicola Calipari only hours after Sgrena's release. Calipari was killed. Sgrena underwent surgery to remove shrapnel from her shoulder.

Sgrena said she may have been deliberately targeted. The White House said the shooting was an accident and promised an investigation. Newsweek correspondent Christopher Dickey speculated that jumpy Americans and reckless Italians share the blame. After all, a compact car speeding towards a checkpoint looks a lot like a suicide bombing in the making.

At Camp Buehring and other U.S. bases in Kuwait, grizzled veterans teach incoming soldiers to treat every oncoming civilian vehicle as a potential threat. “They make them paranoid,” says Staff Sgt. Jeff Wagoner of 2nd Platoon, Charlie Company, Task Force 82, part of the 1st Infantry Div.

2nd Platoon Sgt. 1st Class Rufus Beamon, 34, calls the soldiers involved in the Baqubah shooting “jumpy and stupid.” And some observers say that mistakes by “jumpy and stupid” soldiers will become more common as reservists replace active-duty soldiers in Iraq.

Reservists of all types—including 2,000 members of the Individual Ready Reserve, some of whom left active service more than 10 years ago—now make up nearly half of all soldiers in Iraq and Kuwait, up from 30 percent in 2004, according to the Army.

The 42nd Infantry Division—a National Guard outfit with units based in more than a dozen states including Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York and Vermont—is in the process of replacing the active-duty 1st Infantry Div., which has occupied Diyala province since early 2004. This is the first overseas deployment of a National Guard division since World War II.

The 42nd's deployment and the IRR call-up are just the Army’s latest tacit admissions that it’s in over its head with the occupation of Iraq, which has cost 1,500 American dead, more than 10,000 wounded and hundreds of billions of dollars. And while the Jan. 30 elections were a baby step towards true Iraqi self-rule, the insurgency continues unabated and the potential for bloody civil war between the fractured country’s major ethnic and religious groups grows as Shias consolidate their control over the government.

After two years of fighting, the U.S. Army is all but exhausted. The powerful active-duty force that toppled Saddam Hussein’s government in just weeks has given way to a much smaller active force propped up by reservists.

Full-timers soldiers are only soldiers. They thrive on doing what soldiers do, and doing it well. But reservists are civilians first and soldiers second. Their enthusiasm for the hardships of war and occupation is minimal, and their reservations great. They’re scared and they act like it. And in a place as dangerous as Iraq, fear can kill.

Back in Baqubah on Jan. 29, hearing of the 272nd’s attempts to signal the Iraqi vehicle, Wagoner is dismissive—and angry. “How does that change the rules of engagement?”

Local rules usually prohibit opening fire until an enemy has been positively identified. Suspicion’s simply not enough.

Beamon, Wagoner and the rest of 2nd Platoon are furious. For months, they’ve lived and trained with local Iraqi Army units at Camp Gabe in downtown Baqubah. They eat with the guys. They sleep next door to them. They’re friends.

Wagoner admits that his platoon was nervous and inexperienced, too, when it first arrived in Iraq in February 2004. “We were just like them.”

But 2nd Platoon didn’t accidentally kill any good guys as a result. And 2nd Platoon is active-duty, whereas most of the 42nd’s soldiers were part-timers before they activated for deployment. That means less training and—some say—an increased likelihood of fatal mistakes.

Not so, says Lt. Col. Roch Switlik, a 43-year-old Merck employee from New Jersey and the commander of the New Jersey National Guard’s 50th Main Support Battalion, which hauls supplies and fixes trucks for the 42nd.

“We’re one team,” Switlik says in response to comparisons between active soldiers and reservists. He adds that reservists bring different but not inferior “skill sets” to military operations—like experience in various civilian fields, sometimes years of active-duty experience and “maturity.”

But he admits that in combat situations, part-time soldiers are at a disadvantage compared to their professional counterparts.

As for the Baqubah incident—accidents are “always possible,” Switlik says.

2nd Platoon Staff Sgt. Joshua Marcum, 25, says that in his experience, National Guardsmen are less disciplined than active duty soldiers and more likely to shoot first and ask questions later.

He should know. Last summer, just a few months after he and his comrades arrived at Camp Gabe, a National Guardsman guarding Gabe’s walls opened fire at some Iraqi civilians he mistook for insurgents, killing a 14-year-old girl.

The event was a tragedy for the girl’s family and for Marcum—himself the father of two little girls—but it wasn’t even a blip on international media’s radars, or the Army’s.

The Village Voice was unable to independently verify the shooting. But incidents like the one Marcum witnessed—while not always fatal—are common in Iraq, according to story in the independent Army Times profiling the Army’s efforts to monetarily compensate victims.

“They were just scratching in the dirt, looking for food,” Marcum says of the victim family. His face contorts when he recalls the scene. “I was the one who had to clean up the mess. I carried the girl past that guy and showed him—‘Look what you did, dumbass.’ It was the worst thing I’ve ever seen. And nothing ever happened to that guy [the shooter]. It was just an accident, right?”

Part of the problem is that the nature of the Iraq occupation—in which insurgent fighters and a sometimes hostile but nonviolent population are indistinguishable—makes such accidents more common. Most American fatalities come from ambushes, roadside bombs and suicide bombings.

Only sometimes do insurgents attack in the daytime. Rarely do soldiers see their assailants. Even when they do, the attackers never wear uniforms or identifying marks of any kind. While there is an “insurgent profile” (young, male and pissed), there are always exceptions.

The bottom line is that anyone is a potential killer. And when it comes to bombings, any abandoned car or donkey cart, ditch or pile of garbage could conceal three or four South African artillery shells wired to explode with the touch of a button. Bombs like that have taken out even armored vehicles that were previously thought all but impervious to attack.

All of this makes for fearful soldiers, according to 29-year-old 1st Lt. Kai Chitaphong, a military counselor deployed to Iraq, where he specializes in treating “combat stress”—the Army's term for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. “The worst part is not knowing who the enemy is.”

Hundreds of bombings (Wagoner has survived at least five) have made 2nd Platoon particularly wary of passing cars.

“You get that feeling in your gut whenever a car rolls past,” says Pvt. 1st Class Timothy White, 23. “But what can you do?”

You can shoot first, that’s what. Never mind that most units’ rules of engagements prohibit shooting until you’re certain that a target is hostile.

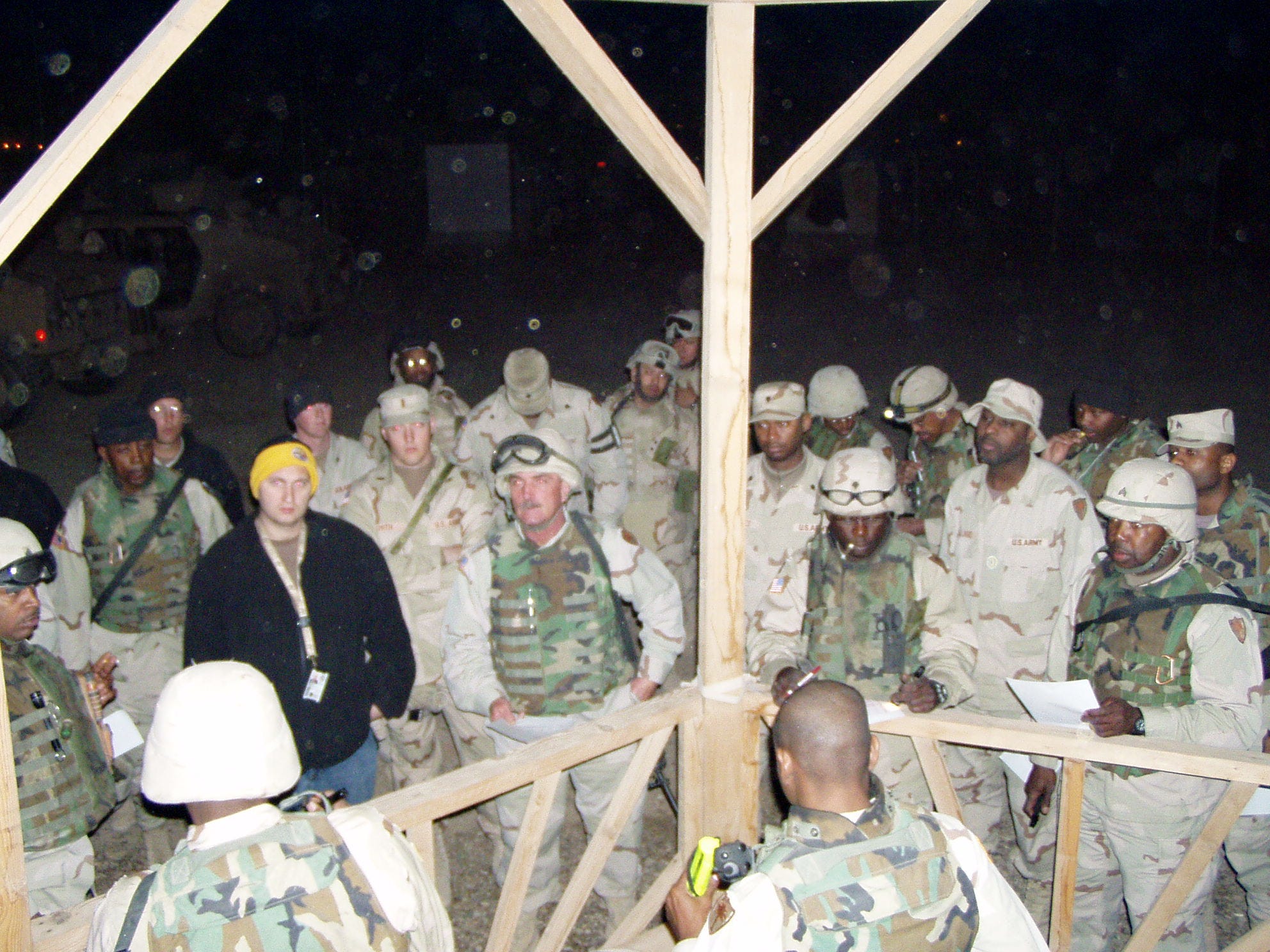

On the morning of Feb. 7, one of Switlik’s platoons led by 1st Lt. Jennifer Wehrle, 33 – a Californian on loan to the New Jersey Guard—gathers on a gravel-covered field in the corner of a former Iraqi air force base near Tikrit. This morning, they'll be hauling 30 truckloads of supplies to the 42nd headquarters 25 miles away. For many, this will be their first mission in a war zone.

The tension in the air is palpable. Another Californian on loan, Spec. Tim Wood, 31, nervously stamps his feet and readjusts his body armor while Spec. Venessa Collins smokes and jokes about how shopping back home in New Jersey is a lot like combat.

“What do you think it's going to be like?” she asks Wood, who just shrugs.

In their brand-new uniforms and armor, these newly-deployed Guardsmen look like toy soldiers next to the seasoned active-duty soldiers from 2nd Platoon. They wear neck armor and knee and elbow pads—items most soldiers see as overkill—even though their convoy is unlikely to draw any fire.

And for a 30-minute mission hauling supplies on heavily-patrolled roads, they sit through hours of briefings and inspections. Most units conducting actual combat missions spend only a few minutes preparing. The overall impression from the Guardsmen is one of over-preparation—and of fear. One briefing highlights attacks that took place months ago on roads on which the convoy won't even be traveling.

And everyone talks about Kuwait, Kuwait.

Before heading into Iraq, most soldiers—and all Guardsmen—undergo varying periods of training in Kuwait, usually at a place called Camp Buehring. Wagoner says this training paints a false portrait of Iraq as a country where the dead are piled on the streets, gunfire erupts from every darkened window and Americans who venture off their bases immediately come under attack by rockets and suicide bombers. “They make them paranoid,” Wagoner says.

This paranoia is in evidence as the convoy crawls out of the base's front gate, stopping briefly to let its handful of gunners shoot two or three rounds into a sand berm—a “test fire,” they call it. 51-year-old Spec. Ernest Benjamin of New York City pulls the trigger on his .50-cal and holds it, spraying rounds up and down the berm. “I live for this,” he says, so high on adrenaline—the chemical product of fear—that you can almost smell it

Less than an hour later, the convoy pulls into its destination. No shots were fired. No suicide bombers took interest. Iraqis waiting in line for gasoline in downtown Tikrit waved as the trucks sped past. Climbing out of his vehicle, Wood looks flushed. “That wasn’t so bad.”

“What I couldn't believe was all the people around,” Sgt. John Branick, 52, says, shaking his head. Branick, a driver here and a mailman back home, sees all Iraqis as a threat—and today, the threat was everywhere. “I mean, they were just out there.”

New Jersey resident Maj. Michael Lyons, 40, Switlik’s second in command, says that his troops are just “green”—inexperienced—and that it’s a problem not only with Guardsmen, but with any soldier new to Iraq. He says that may have been a factor in the Jan. 29 shooting.

Besides, he adds, the average Guardsman has more experience in the military—if not in actual combat—than the average active-duty soldier. Many older soldiers spend the last years of their enlistments or commissions in the reserves, where they train only a few weeks per year and can devote themselves to new civilian careers and to their families.

But tactical skills—like knowing when to shoot and when not to—decay quickly if you don’t exercise them every day, says Texan Capt. Stephen Short, 41, an officer with the Tennessee-based 467th Engineer Battalion, 50 of whose 115 members were recalled from the Individual Ready Reserve, some after years of civilian life. Short himself came from the IRR. “Tactically,” he admits, “We’re at a disadvantage.”

This disadvantage can be fatal to innocent Iraqis caught in reservists’ crosshairs.

Read more:

The Dread Zone

Between February 2005 and March 2006, I traveled to Iraq several times for The Village Voice—the New York City alternative newspaper that folded in 2017 and now reappears only sporadically. I wrote 16 stories for The Village Voice. The paper paid me $1,000 for each, essentially launching my writing career.