Between February 2005 and March 2006, I traveled to Iraq several times for The Village Voice—the New York City alternative newspaper that folded in 2017 and now reappears only sporadically. I wrote 16 stories for The Village Voice. The paper paid me $1,000 for each, essentially launching my writing career.

This story The Village Voice appeared in April 2005. It’s about what was, at the time, the worst city in Iraq—Mosul. A future battlefield in the next war. The war with Islamic State.

“It’s a fox.”

Sgt. Tracy Toliver, 33, is gazing through the infrared sights of his Stryker armored vehicle at something creeping along the desert nearly a mile away in the dead of night. From this distance, in these conditions, with this equipment, all he can make out is a pair of glowing green eyes and four little legs.

He scowls. “No, it’s a ferret. It’s a ferret!”

It isn’t a ferret. Nor does it matter. At this point -- a couple of hours into a late night patrol on the sandy outskirts of Mosul, Iraq, on March 25, 2005—the American and Iraqi soldiers of 2nd Lt. Tom Burns’ four-vehicle patrol from the Ft. Lewis-based 25th Infantry Division, deployed near the town of Qayyarah, are really just killing time.

It’s cold. It’s windy. Everybody’s tired. And they haven’t seen anything all night.

One soldier in the back of the Stryker—a long boat-shaped vehicle with eight tires and a missile launcher—is fast asleep. The driver, Capt. Kyle Pennington, 26, hasn’t made a peep in half an hour. Burns, 22, fresh out of his post-college basic officer’s course and only three weeks in country, is tinkering with the infrared sight, trying to figure the thing out. And God knows what the Iraqis are up to, huddled with their AK-47s in the back of their Toyota pick-ups. Even the best Iraqi soldiers are little unreliable by American standards.

Burns steers his sight left. He steers it right. He spots a flock of American helicopters darting on the horizon, headed who-knows-where.

Then he sees it—a lone pickup truck tearing down a remote road.

He springs into action. Firing up a radio, he orders two Iraqis from one pickup to hop into the back of the Stryker. He may need them to talk to whoever’s in the mysterious truck. And where Burns is going, no mere Toyota can follow. He tells Pennington to catch that truck.

The Stryker roars to life and lurches forward, speeding down a steep hill and across the sandy wastes at more than forty miles per hour, churning up an opaque cloud of dust that reflects the full moon. It’s a Hell of a rough ride; the Iraqis in the back are grinning and shaking like honeymooners on a vibrating bed. And Burns, he loses sight of the suspect truck on account of all the commotion.

No problem. It was probably nothing. Probably not an insurgent with a bed full of RPGs. Probably not a budding suicide bomber en route to some crowded marketplace in downtown Mosul. Probably not Abu Musab Al Zarqawi, the most wanted man in half-a-dozen countries. Probably nothing to disturb hard-earned relative peace of this cold desert, the front door to one of the most dangerous cities in Iraq, a desert patrolled by just 300 Americans from wet, green Washington state.

Back to the hill they go. Back to their pickup go the Iraqis. Back to sleep goes the soldier in the rear.

Some time later, Toliver spots something with glowing eyes and several legs. “It’s a dog!”

For a while, it was Nasariyah. Then Karbala, Ramadi, Anbar province. Then maybe Baqubah. Baghdad’s always a close second. But for the past few months, the worst place in Iraq has been Mosul.

The criteria are hard to quantify. A certain number of suicide bombings are required. Violent death is part of the equation. But it’s more than mere arithmetic (no. attacks x avg. body count/time span); there’s an almost atmospheric quality to the worst place in Iraq.

Wherever you get this really bad feeling just walking the streets, wherever the walls of your barracks seem to curl in around you, wherever the food tastes wrong, the air seems stale and the local fauna look … apprehensive, this is the place.

This is where you don’t want to get deployed. This is where you don’t want your helicopter dropping in for gas. If you’re an American soldier on a bus somewhere—in Kuwait, maybe—and some rear-echelon type asks you where you’re headed, and you say, “[Fill in blank],” then they wince and say, “That sucks!”—that’s when you know.

There’s a reasonable explanation for the problems in Mosul. For much of 2004, Fallujah was an insurgent stronghold. But in November 2004, the U.S. military unleashed an over-gunned force of tanks, artillery and blood-thirsty Marines on Fallujah, all but leveling the city and killing hundreds of insurgents.

But the smart ones hit the road, heading north along the main highway, heading to Mosul, an impoverished, ethnically-divided city ripe for a little bloodshed. And they decided to stop along the way, in Sunni Qayyarah and its surrounding towns and villages, collectively known to Americans as Q-West.

“It all happened in two weeks,” says Lt. Col. Bradley Becker, commander of 2nd Battalion, 8th Field Artillery Regiment—Burns’ unit—which since October 2004 has patrolled the approaches to Mosul.

In the wake of the Fallujah fight, Q-West, which had been pretty peaceful to that point, “fell apart,” in the words of Maj. Kevin Murphy, 36, a Seattle resident.

It didn’t help that insurgents’ flight from Fallujah coincided with Ramadan, the Muslim religious holiday that, last year, inspired anti-American violence all over the country.

All over Q-West, police stations were attacked. Iraqi Army bases were attacked. Most Iraqis in uniforms here decided that being Iraqis in uniforms was bad for their health. They deserted by the thousands. Meanwhile, people were dying in the streets.

“I went from 2,000 police to 50,” Becker says, adding that there was a similar exodus in the Iraqi Army. “Let me tell you, there were some sleepless nights.”

Fires burning all around them, 2nd Battalion swung into action, pushing out as many armed patrols as possible and launching a crash program to restore security—which, with so few Americans in such a large place, meant reforming Iraqi forces to do the bulk of the work.

And that meant firing all the cowardly old Iraqi officers and police chiefs—the ones that could still be found, that is—and replacing them on the fly with anybody who had any qualifications and a backbone. Ra’ad, a former soldier running a private security company at a refinery in Qayyarah, found himself with a brand-new colonel’s commission from the Americans after he voluntarily fought back against insurgents.

Taking back Q-west has been messy. But through it all, 2-8’s been lucky. Despite the level of violence and the number of native casualties, not a single soldier from the unit has been killed in Iraq, and only five wounded.

But their luck can’t hold forever—and besides, Becker’s goal is to begin completely turning over Q-West’s security to Iraqis in July 2004. It’s an ambitious goal in a country where decades of tyrannical top-down leadership bred cops and soldiers who caused more problems than they solved.

The stakes are high. A key to peace and stability in Mosul is keeping bad guys and guns out. And the key to keeping bad guys and guns out of Mosul is securing the highway, the Tigris River and all the little towns and villages in Q-West. And while 2-8 can jump start security here, only Iraqis can drive it home.

“Local cooperation is the key,” says Capt. Mike Yea, 29, one of Becker’s staff officers. The way he describes it, Q-West residents keep an eye on their own streets and report anything suspicious to the police, who do what they can and call on the Iraqi Army when they’re outgunned. The Iraqi Army, in turn, calls on 2-8 when it’s outgunned. The idea is to let Iraqis solve their own problems until the problems spin out of control.

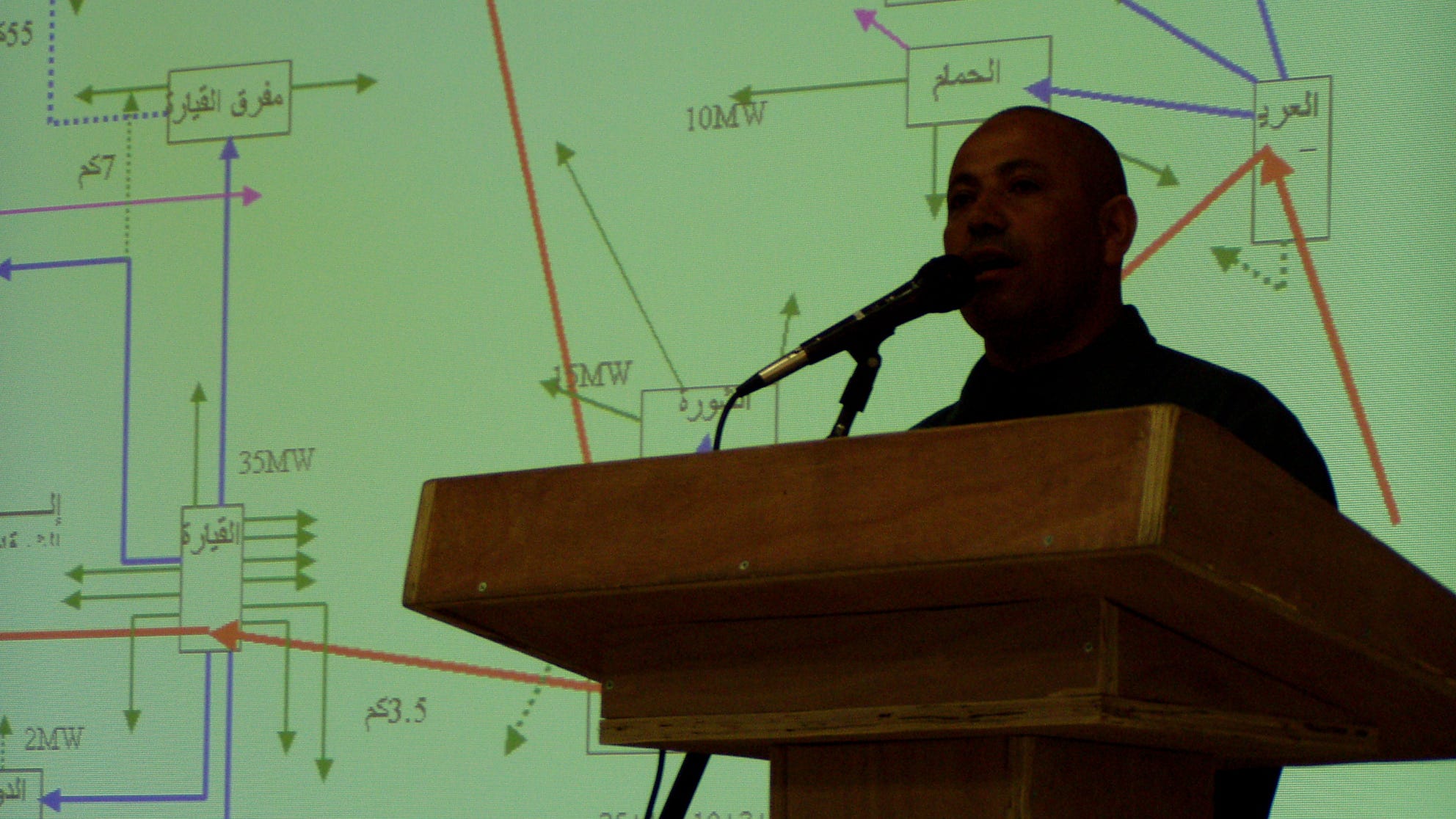

“Case in point,” Yea says, planting a finger on a map pegged with color-coded flags representing Iraqi Army checkpoints and outposts. Under his finger, bristling with flags, is a town named As Shura.

When 2-8 arrived in October 2004, As Shura was the worst place around. And in November 2004, its police stations were blown to pieces by insurgents. So 2-8 built a fortified outpost downtown and packed it full of recently-recruited Iraqi soldiers and a handful of American babysitters.

Now, troops in As Shura get as many as six tips per night, says 1st Sgt. Darren Kinder, 40, from Delta Co., 52nd Infantry. Kinder‘s unit—attached to 2nd Battalion—maintains round-the-clock presence at the outpost alongside the Iraqis. “Some tips pay off, some don’t,” Kinder says. “We’ve asked the local populace to step up, and they’ve been responding fairly well.”

On March 25, 2005, Lt. Burns and his patrol stop in As Shura to check on the outpost. Inside, Americans and Iraqis sprawl around a table playing cards. Later, back at 2-8 headquarters, Becker and Murphy head to the roof to smoke cigars. “The fact that we can all relax like this is a good sign,” Becker says. But these moments of leisure are the result of a lot of hard work.

“We rely heavily on [local] leaders to find out about terrorist activities,” Yea says. But connecting local leaders—tribal sheiks and Muslim imams—to native and U.S. forces means meeting them, winning their trust and convincing them that siding with the new government and its U.S. masters is a winning proposition.

It’s a tall order, and it falls on the shoulders of officers like Capt. Ryan Gist, 29, and 1st Lt. Todd Cody and soldiers like Spec. Harvey Blankenship, 22, a native of Chehalis. On March 27, 2005, they set out early in a patrol of armored Humvees to make their rounds. First stop is a market in downtown Qayyarah, where meat vendors slaughter cows on the sidewalk and frothy blood runs in gutters swimming with trash.

Gist, Cody and a translator greet vendors and private security guards in Arabic and chat them up while Blankenship and other young soldiers stop traffic, search the occasional truck and keep an eye out for anything suspicious.

Suspicious like the Iraqi teenager strolling the nearby bank of the Tigris in an Iraqi Army bulletproof vest. Saying goodbye to a vendor—who gets back to slicing the hooves off of a dying cow—Gist and the others trot toward the teenager with their rifles aimed at his chest.

The kid ditches the vest and raises his hands. Seeing that the kid’s no threat, Gist makes nice. No sooner has he sent the boy on his way than Blankenship spots a fishing boat trawling up the Tigris. Gist waves it in; it beaches near several fishermen making camp around a dying fire. A transistor radio warbles Arabic pop music.

Gist introduces himself and makes some stilted conversation in Arabic before switching to English. His translator listens carefully to everything Gist says before turning to the fishermen and repeating in Arabic, complete with all the right furtive hand gestures and facial ticks.

“Seen anything on the river?” Gist asks.

“La’a,” a fisherman says. No.

Behind them, soldiers search the fishing boats and turn up … fish.

“Terrorists have been using the river,” Gist says. “We need you to keep us informed.”

But never mind all that. “How’s the fishing?” Gist asks.

A five-minute discussion of local and American fishes ensues. As Gist says his goodbyes and moves to leave, one fisherman darts to his boat and dangles one slippery silvery fish by its gills, offering it to Gist.

“Oh, no thanks,” he says. “Where would I put it?”

They hit the road and head across Q-West, stopping at a gas station, police stations and the Qayyarah oil refinery. Around noon, the patrol pulls onto the groomed, green and walled lawn of one of Q-West’s movers and shakers, Sheik Ishmael. Kids play outside. Servants tend the sheik’s house and its grounds.

Again, Blankenship stands guard while Gist and Cody have all the fun. Handshakes and kisses, then the officers move indoors at the sheik’s elbow.

He’s a stout, clean Sunni with a trim mustache and a cigarette always in one hand. He presses the Americans into chairs and barks at a boy to prepare coffee and chai, the sweet sugary hot tea served in tiny glasses at every occasion in Arab countries.

“I consider you my brother and my friend,” Gist says to Ishmael as he sips his chai. And then he leans forward and listens as Ishmael talks.

And talks.

And talks.

For more than an hour, Gist nods gravely as Ishmael cites a litany of problems—chief among them, unemployment and an electricity shortage. Gist promises that the government is doing all it can do address the problems. Then he sounds his refrain.

“We can’t do this without you,” he says. “We need you to tell us where the problems are.”

Ishmael thinks a moment then lists the towns and villages that need attention. Cody, sitting at Gist’s side, takes careful notes.

Outside, Blankenship is besieged by ratty, buck-toothed Iraqi kids on their way to school. He tries to ignore them as they dance around him yelling, “Mister! Mister! Pencil, Mister?”

Apparently, pencils are hard to come by here.

“It’s a big culture shock to see how they live,” Blankenship says. “But we’re doing them good. We’re not going to see massive change in their culture overnight.”

He mentions the main conflict in Iraq: ethnic and religious rivalries. “I mean, we had discrimination in the States, too.”

His use of the past tense is striking, for Blankenship is an Asian American; his ancestors weren’t always welcome in the U.S. But things are better now. At least there’s no slaughter in the streets, like there is in Mosul, and like there was here in Q-West just months ago.

Blankenship shrugs. “Progress might take a century.”

In the meantime, 2-8 does what it can to keep the peace. That means long nights chasing ferrets and elusive trucks. It means chatting with fishermen and drinking chai with sheiks to keep the locals on your side. It means standing there with your rifle watching Iraqi kids walk to school.

It means doing everything possible to keep bad guys and guns out of Mosul.

On the cold night of March 26, 2005, Becker’s headquarters is buzzing. In one corner, Yea is staring at his map with its colored flags. In another, Command Sgt. Maj. Victor Martinez, Becker’s top enlisted man, leans arms-spread over another map—this one highlighting the wide snaking length of the Tigris River as it nears Mosul.

He says he’s thinking of strapping a machine gun to a houseboat to patrol the river. Someone laughs until they realize Martinez is not really kidding. In a third corner, Becker pow-wows with a bunch of grinning enlisted men with rifles slung over the backs and helmets under their arms. They’re all drivers in a convoy that’s leaving in the morning. Becker briefs them on their destinations.

When he says, “Mosul,” every grin goes flat.

Q-West isn’t bad, thanks to 2-8—to soldiers like Burns, Murphy, Yea, Gist, Cody, Blankenship and Becker. And it’s getting better. But Mosul … well, despite 2-8’s best efforts, bad stuff gets through. And in Mosul, that equals explosions, gunfights, death.

Nobody likes Mosul.

Read more: