The Supermarine Nighthawk Was a Bizarre, Zeppelin-Hunting Flop

A young designer who later built the Spitfire learned a few lessons

by ROBERT BECKHUSEN

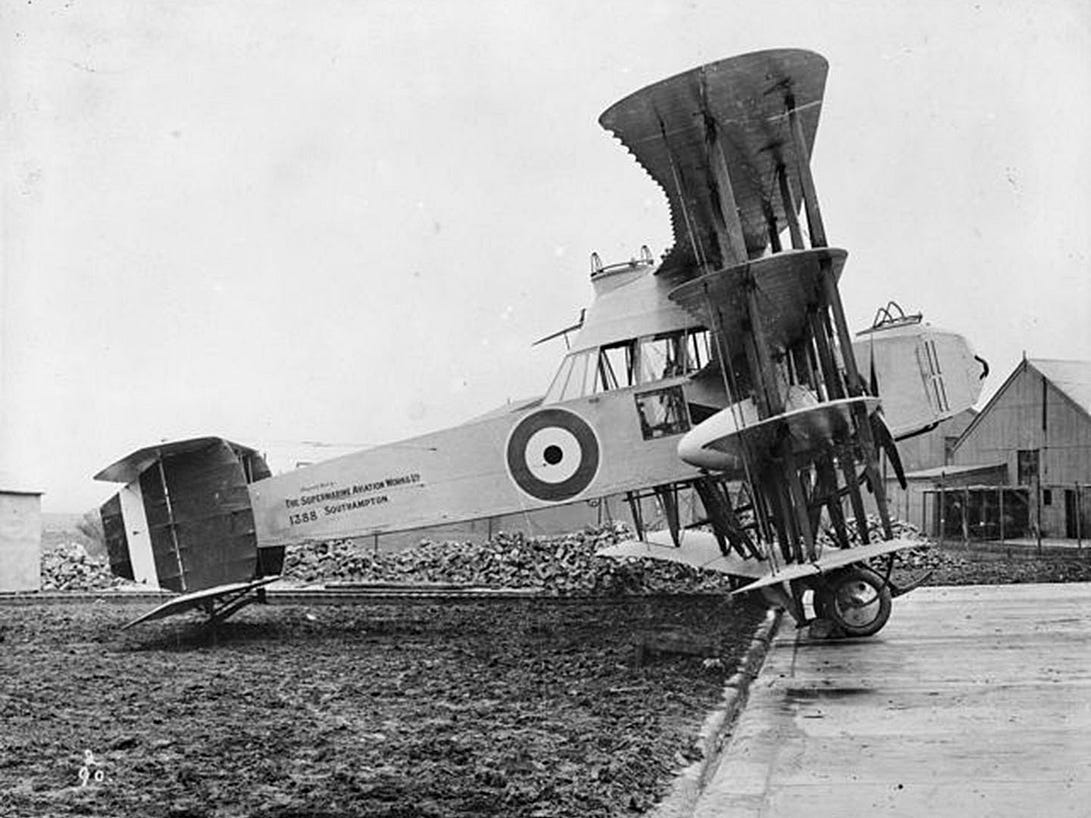

World War I produced some truly ungainly aircraft designs. The Supermarine Nighthawk was one of the weirdest looking of all, and had the peculiar purpose of shooting down zeppelins—though it never fired a shot in anger.

The Nighthawk was the product of the influential British aerospace company Supermarine Aviation Works, which went on to develop the highly successful Spitfire in 1936. But in 1917, a young R.J. Mitchell—the Spitfire’s chief designer—was a young employee at Supermarine when he encountered the bizarre P.B. 29E, the Nighthawk’s predecessor.

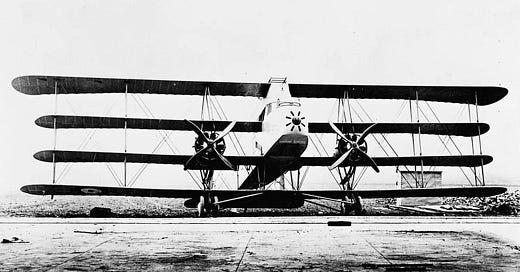

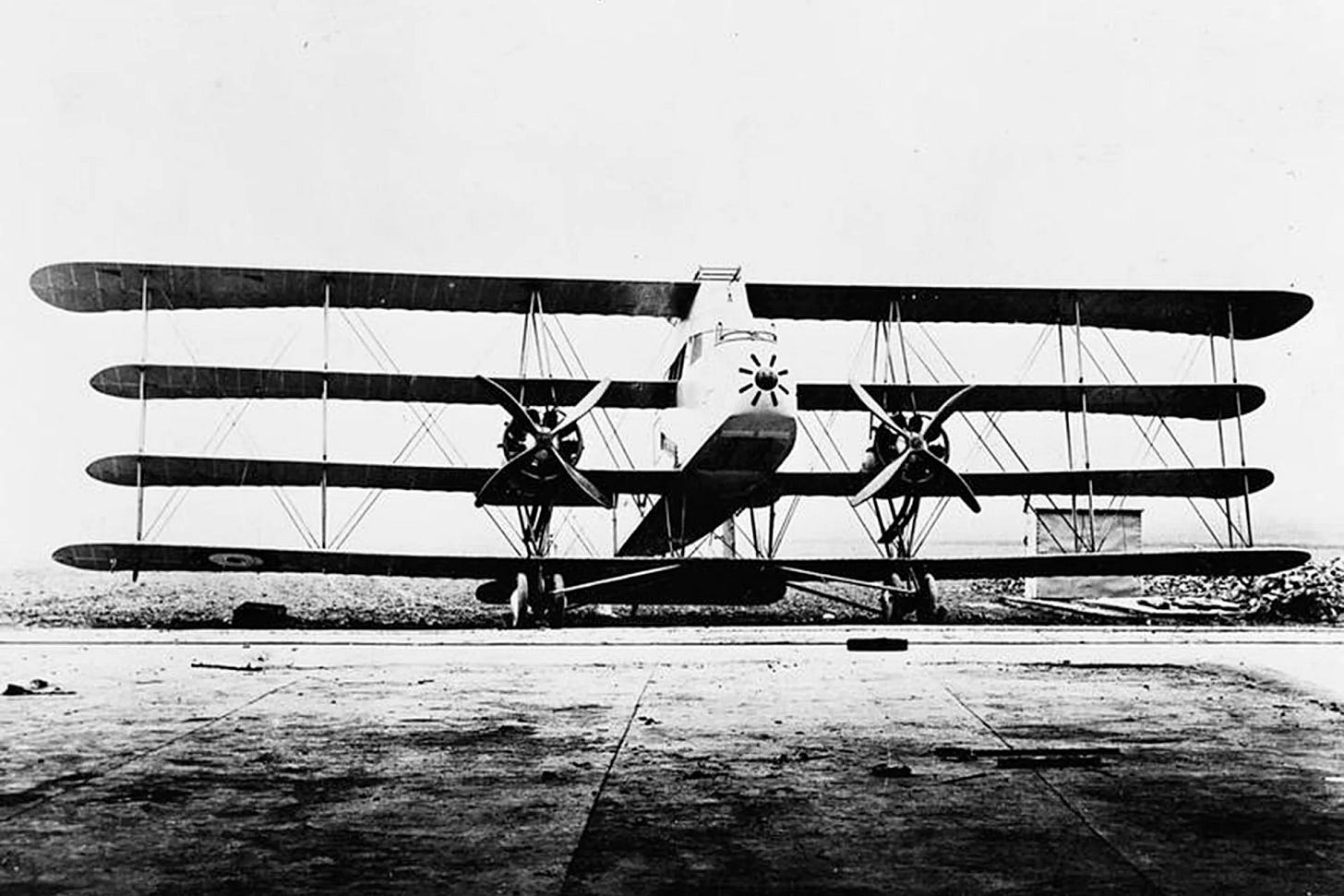

It couldn’t have looked more dissimilar to the aircraft that defined Mitchell’s later career. The P.B. 29E, and the follow-up Nighthawk, looked like a flying set of construction scaffolding.

P.B. 29E would crash during a test flight. The Nighthawk, or P.B. 31E, was just as unusual. The aircraft was an enormous quadruplane, nearly 18 feet high with a wingspan of 60 feet. The four stacked wings provided a large surface area while being relatively light, an engineering concept designed to allow the Nighthawk to intercept German airships at high altitudes.

Zeppelins raided Britain dozens of times in the war, and while they had no effect on the conflict’s outcome, they killed hundreds of civilians and were a terrifying presence for a population unaccustomed to strategic bombing.

The Nighthawk was able to reach relatively high altitudes for the time, but it would’ve taken a long time getting there. The plane’s two underpowered engines meant it took an hour to reach 10,000 feet, according to John Shelton’s book From Nighthawk to Spitfire: The Aircraft of R.K. Mitchell.

Problem was, that was still several thousand feet below the operating altitude of mid-level zeppelins, and couldn’t come close to high-climbing ones. The Nighthawk would’ve likely been limited as an interceptor.

Its maximum speed was 75 hours in theory … a measly 60 in practice.

A movable searchlight—with a separate power source—on the plane’s nose and a 37-millimeter Davis gun on the top served as its main zeppelin-hunting equipment, as the airships typically carried out raids at night to avoid ground-based artillery.

Two .303 Lewis guns rounded out the armament. Four crew members, including two gunners, manned the plane.

The Nighthawk’s performance was … not good. The P.B. 31E—which Mitchell worked on—had poorer performance than Supermarine advertised. “Mitchell, therefore, must have learned swiftly how aircraft designs were, more than anything else, at the mercy of engine technology,” Shelton wrote.

It should come as no surprise that the awkward Nighthawk never saw combat, and Supermarine went on to scrap P.B. 31E.

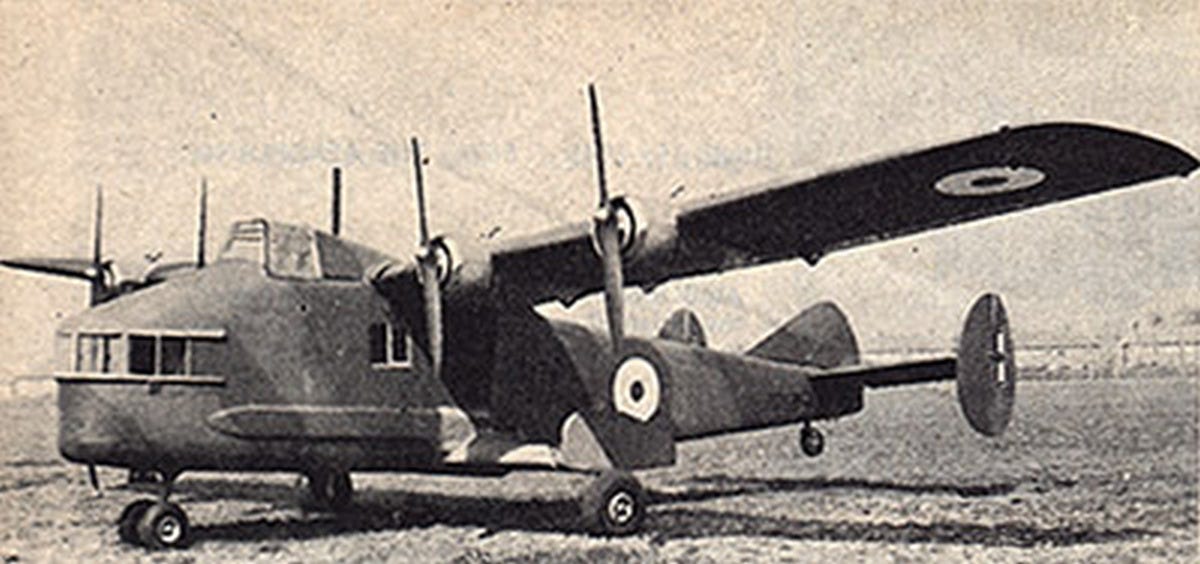

There was a better way to shoot down zeppelins. Step one—find a better fighter, which Britain did with the Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2, a stiff plane found incapable of dogfighting. But it was a stable platform for attacking airships, and British pilots took to firing on zeppelins from below with a mix of explosive and incendiary ammunition to puncture and light them on fire. It was a successful tactic.

The Nighthawk became an ugly footnote. But people learn through failure—or at least by failing well. Mitchell surely took a few lessons from the Nighthawk.

Read more: