I had just stepped into the Australian army’s makeshift latrine—a hole in the ground surrounded by a canvas screen—and unzipped my fly when, just over the wall of the boys’ school, there was a thunderclap, a spout of smoke and dust, earth and what appeared to be body parts tumbling through the air.

I stumbled out of the latrine, fumbling with my zipper, looking for my cameras, my helmet, my body armor. A dozen Australian soldiers, just moments ago lounging in the shade with their weapons by their sides and paperback novels in their grimy hands, were now on their feet, frantically strapping on their armored vests, checking and re-checking their weapons, looking to their lieutenant for direction.

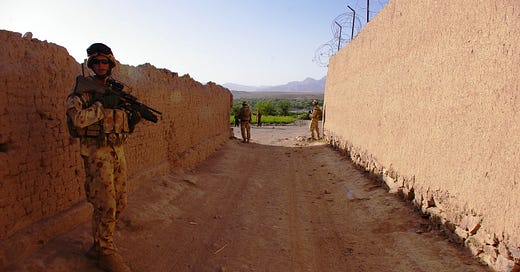

Lieutenant Cliff was on the radio asking his captain for orders. The Aussies had come here to Tarin Kowt with a handful of army engineers driving bulldozers and steamrollers to rebuild the school’s cratered soccer field while, down the road at a girls’ school, a Dutch army delegation of women soldiers and reporters attended a ceremony with local Afghans to celebrate International Women’s Day.

It was all part of the coalition’s strategy for winning over the xenophobic tribespeople of Uruzgan province, a Taliban stronghold. The Aussies had expected reluctance, even resistance, but they hadn’t expected explosions and flying body parts.

But this was Afghanistan in June 2007, a dangerous place in its most dangerous season, six years into the U.S.-led war to eradicate the radical Islamist Taliban. It was best to expect the worst.

Smoke was spreading from the blast site. In the distance, a child was wailing. That confirmed for me that the Women’s Day delegation had been the target. It was Friday, so school wasn’t in session, but anywhere there are festivities—and especially anywhere there are cameras—Afghan children are drawn.

Just moments before the blast, I’d hiked down the road with my bodyguard, a Dutch sergeant, to peek at the Women’s Day crowd gathering around the Dutch vehicles in a narrow alleyway. A blast in that space would make puree of unarmored bodies.

I wanted to go there, to help if I could, but also just to see, to prove to myself that the Taliban were as truly bad as their reputations. Endless days patrolling poor, dirty, ambivalent towns have a way of sapping your will to hate and your ability to believe in something as clear and simple as an enemy.

In the developing world’s ancient morass of crime, corruption and tribal conflict, it’s often easiest to accept even the worst violence as simply part of the landscape rather than as something deliberately perpetrated by evil men. After three years of awful ambiguity in places like Iraq, Lebanon, East Timor and Afghanistan, I needed some clarity. And I needed to act.

I wasn’t alone. The Aussie soldiers bounced on their heels, fists clenched, eyes wide. They too were desperate to do something, anything—perhaps even more so than me. After all, they’d spent years training for this. But they’d also trained to follow orders, and the orders relayed through Lieutenant Cliff were to stay put. The Dutch had an ambulance on the way, headquarters said, so stay put, keep up your guard, and await further orders.

But staying alert in the 110-degree heat was next to impossible, and within an hour the Aussie soldiers were sprawled in the shade again with their paperbacks, only occasionally glancing in the direction of the girls’ school at the still-rising column of smoke. I ventured back to the latrine to finish what I had started.

But warily, for three years as a war correspondent had made me superstitious about simple acts like using the bathroom. Any time you let down your guard, something bad will happen. That was a view shared by an Australian sergeant who told me that every time he tried to take a shit in Afghanistan, he got attacked by the Taliban.

I closed the canvas screen. I unzipped my fly. I took a deep breath. And in the distance, something exploded. Again I raced out, cursing, only to find the Aussies strangely calm and my bodyguard staring at the horizon with a far-away look in his eyes. “Dutch artillery,” he whispered.

At least eleven people died in that blast. It’s hard to say for sure because there were lots of kids on the street and their tiny bodies were smeared on walls and heaped in meaty piles. The lucky ones died in an instant. Others, like 20-year-old Dutch private Timo Smeehuyzen, took some time.

The day after the attack I watched some video shot by a Dutch reporter in the targeted convoy. One second she’s zoomed in on three Dutch soldiers—Timo on the left—poking their heads out the top of their armored personnel carrier. The next there’s nothing but dust and noise.

Cut. Now the tape shows the charred personnel carrier, its rear ramp thrown open, three Dutch bodies sprawled inside—and on the ground all around, dead kids.

Dutch medics race to aid their injured friends, leaping over piles of smoldering flesh that are barely recognizable as the remains of 10-year-old boys. The medics help two of the wounded troops to their feet and walk them clear of the vehicle. But Timo just lies there, the tips of his tan boots pointing straight into the air.

Cut. Now a medic is giving Timo chest compressions. Another soldier is running between two vehicles, breathlessly delivering messages. Timo is still alive. Where’s the ambulance? Somehow the look in his eyes is more terrifying than even the sight of the dead boys’ broken bodies in the background.

Cut. An hour later. The ambulance has arrived, but too late. Timo is dead. The camera focuses on a young Dutch soldier riding shotgun as the convoy winds through Tarin Kowt’s deserted streets. His eyes are alert, scanning left and right for Taliban attackers. But his cheeks are pink and streaked with tears.

It took me a full day to get back to the Kamp Holland, the main Dutch and Australian base just five miles from Tarin Kowt. As we arrived I saw, on a distant hilltop, a Dutch howitzer with its long barrel pointed towards the Chura valley, 20 miles away, through which the Taliban smuggle opium, weapons and new recruits to and from Pakistan.

Every few minutes the howitzer fired, kicking up a cloud of dust and sending shock waves rolling through camp.

The suicide bombing, it turned out, was just the opening shot in a massive Taliban assault across three provinces. Suicide bombers struck an Afghan police bus in Kabul and a Canadian patrol in Kandahar while Taliban fighters fired mortars, rockets and machine guns at Afghan police checkpoints in Tarin Kowt and Kandahar.

When the police fought back, the Taliban kidnapped their families, executed some and held the others hostage. Coalition forces surged to reinforce the battered Afghans. In five days of combat all over southern Afghanistan, hundreds of people died. It was brutal.

On the fourth day of fighting in Tarin Kowt, a grave-faced major announced that another Dutch soldier had died when his mortar tube exploded, either by accident or when a Taliban shell landed directly on top of it. Later, a Dutch soldier approached me as I sat sipping my second cappuccino at the base mess hall.

As the resident American, I was assumed to be an expert in wartime sacrifice. After all, as many Americans had died in Iraq and Afghanistan as Dutch had even served there. “If it was an accident,” he said, referring to the dead mortarman, “is he still a hero?”

I didn’t

know, for in this nasty little war in this nasty little country, concepts like heroism seem out of place. No one person’s sacrifice will end the opium trade, reform the Taliban or save the Afghans from a history of military occupation and economic repression.

Afghanistan rewards skepticism, long-suffering and a tough bladder. But not heroism. For when something bad happens, most of us are too far away to help or ill-equipped for the job, or someone in charge tells us to stand by, keep up our guard, await further instruction. Afghanistan denies us the heroic acts we all long.

That’s the truth, but it’s no comfort to a grieving survivor. So I lied.

“Yes,” I said. “He’s a hero.”

Read more:

Begging to Linger at the Shuffling Parade of the Dead and Damned

Another day, another convoy. More than a week into my January 2005 embed with the South Carolina National Guard’s 1052nd Transportation Company, hauling supplies across Iraq from Anaconda, a logistics base in Balad, I didn’t have jack shit to wri…