Twenty-One Years Ago, the U.S. Military Tried to Record Whole Human Lives. It Ended Badly.

Before Facebook, the military tried to make an all knowing 'cyberdiary' called LifeLog.

In mid-2003, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency launched an ambitious program aimed at recording essentially all of a person’s movements and conversations and everything they listened to, watched, read and bought.

The idea behind the LifeLog initiative was to create a permanent, searchable, electronic diary of entire lives. Not only would a lifelog immortalize users, in a sense, it would also contribute to a growing body of data that military researchers hoped would contribute to the development of artificial intelligence capable of thinking like a human being does.

LifeLog was an iPhone before there were iPhones, social media before there was social media. It was potential all-seeing government surveillance before anyone worried about the NSA or had heard of Edward Snowden.

LifeLog arguably was years ahead of its time. But today, it’s just a footnote in tech history. Barely a year after it began, the LifeLog program abruptly ended, effectively shamed out of existence by privacy-advocates and the media.

And then, over the following decade, much of what LifeLog aimed to achieve happened, anyway. A failed military cyber-diary from 15 years ago was, in a way, a preview of our smartphone-addicted, Facebooking, government-surveilled present.

At the same time, LifeLog was “a cautionary tale regarding privacy controversies,” its creator Douglas Gage told me during a series of phone and email interviews.

The ideas behind LifeLog are much, much older than the program itself. In 1945, a government scientist named Vannevar Bush described an idea he termed “Memex.” It was, in some ways, a prescient flash forward to smartphones.

Memex, Bush wrote in The Atlantic in 1945, would be a “device in which an individual stores all his books, records and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility.”

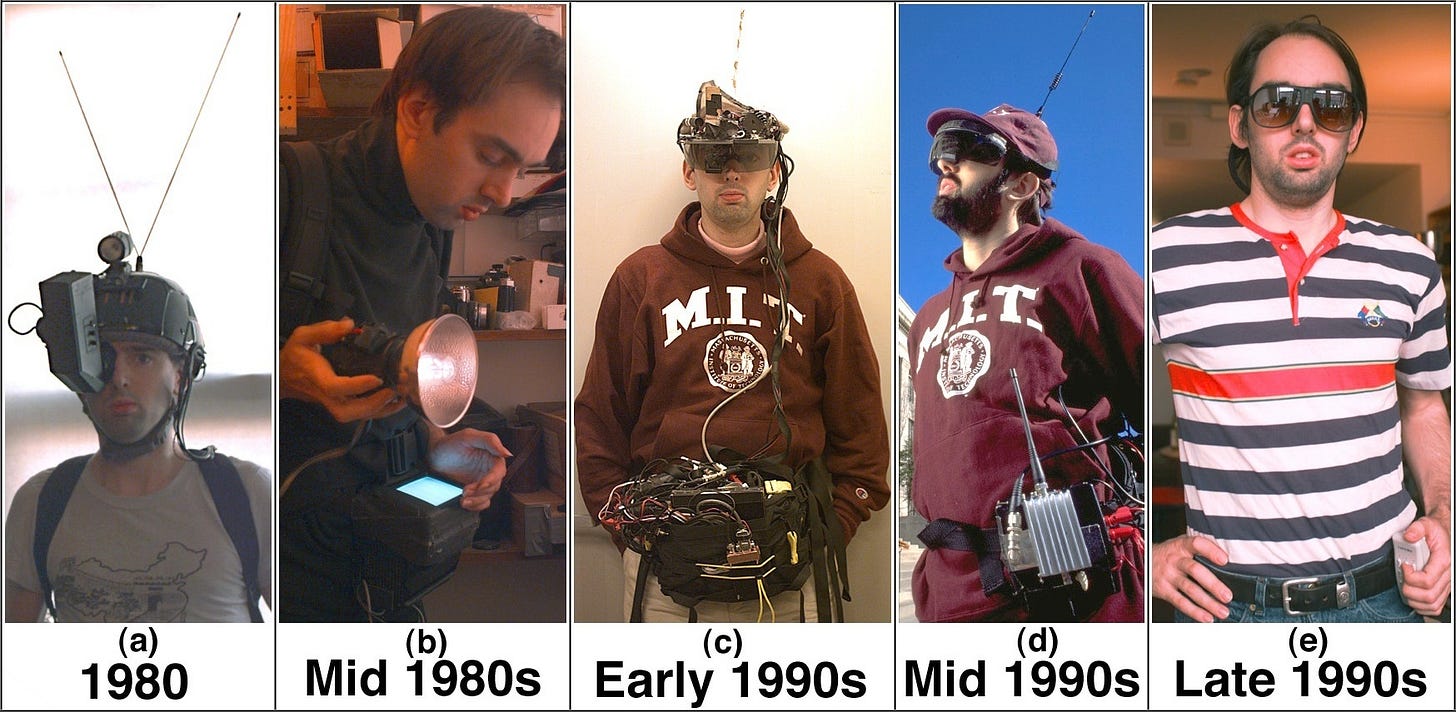

Of course, 1940s technology wasn’t up to the task of recording a person’s every conversation and everything they read. It took nearly 70 years for the tech to catch up to Bush's vision. In late 2001, Gordon Bell, a computer scientist consultant, volunteered to be the subject of MyLifeBits, a life-logging experiment run by computer scientists Jim Gemmell and Roger Lueder for Microsoft.

For 17 years running, Bell has digitized and saved, well, everything. “A lifetime’s worth of articles, books, cards, CDs, letters, memos, papers, photos, pictures, presentations, home movies, videotaped lectures and voice recordings,” according to the project’s website.

In later years Bell added phone calls, instant-messaging transcripts, television and radio to his record. Meanwhile, Gemmel and Lueder wrote software for indexing and searching Bell’s log.

To the experiment's architects, its value was self-evident. “Given only one thing that could be saved as their house burns down, many people would grab their photo albums or such memorabilia,” the three men wrote in a 2002 paper.

DARPA, however, saw the military value in a comprehensive record of a person’s life. In late 2002 the agency had launched a wide-ranging effort to develop new, more sophisticated artificial intelligence. The $7.3-million Cognitive Computing initiative included an “enduring personalized cognitive assistant”—basically, an artificial intelligence secretary that could learn by watching.

To replicate human decision-making, the A.I. assistant would need data on human behavior. Lots of it. Gage, a former Navy researcher with more than 25 years’ experience, had recently joined DARPA. He had a plan for gathering that data. “I hate to say ‘Orwellian,’ but I think that’s what my reaction was.”

Drawing inspiration from Bush and Bell, Gage proposed LifeLog. If enough people recorded enough of their lives, the combined information would amount to “the ontology of a human life,” Gage told me.

His bosses liked the idea. “DARPA clearly saw how increasing digitization of human experience would make the data needed to model everyday life accessible in machine-readable form,” Lee Tien, a privacy lawyer with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, told me.

Gage got initial approval for his project and, in December 2002, began workshopping the idea with fellow scientists and engineers. “The research community was very enthusiastic,” Gage told me. “My father was a stroke victim, and he lost the ability to record short-term memories,” Howard Shrobe, an MIT computer scientist, told Wired in defense of LifeLog. “If you ever saw the movie Memento, he had that. So I’m interested in seeing how memory works after seeing a broken one. LifeLog is a chance to do that.”

Privacy advocates, by contrast, reacted with revulsion. “I hate to say ‘Orwellian,’ but I think that's what my reaction was,” Steven Aftergood, an analyst with the Federation of American Scientists, told me. “It seemed like a massively intrusive initiative that went far beyond what an ordinary person would willingly and knowingly consent to.”

In 2003, Aftergood, Lee and other experts were on high alert for new, potentially intrusive surveillance technologies. In February of that year, DARPA had launched a new surveillance effort it called “Total Information Awareness.” TIA’s sophisticated software cross-referenced phone calls, internet traffic, bank records and other personal data in an effort to identify potential terrorists.

Congress shut down TIA after just a few months. But for Gage and DARPA, the damage was done. “LifeLog has the potential to become something like ‘TIA cubed,’” Aftergood told Wired at the time.

Gage told me the criticism took him by surprise. “[Journalist Noah] Shachtman’s Wired article was the full flowering of paranoia,” he told me. Gage said he never intended for LifeLog to spy on people. “The critics completely mischaracterized LifeLog as a collection system, when the focus was the classification and fusion of low-level multidimensional data to infer higher level ‘knowledge’ of the course of a single person’s life.”

Gage insisted that LifeLog users would be able to choose which facets of their lives the system recorded, and who had access to the resulting data.

But the pamphlet DARPA handed out to researchers who might want to join the LifeLog program did point to LifeLog’s potential as a surveillance tool. “LifeLog will be able … to infer the user’s routines, habits and relationships with other people, organizations, places and objects,” the pamphlet explained, “and to exploit these patterns to ease its task.”

News of the program spread.

In June 2003, The New York Times’ William Safire blasted LifeLog as an

“all-remembering cyberdiary” with insidious side-effects as people became walking government data-collectors. “Everybody would be snooping on everybody else,” Safire warned.

LifeLog's problems multiplied. In July 2003, DARPA began offering grants in support of Gage's work. The grant guidelines seemed to underscore the privacy concerns. “Researchers who receive LifeLog grants will be required to test the system on themselves,” Shachtman explained in a July 2003 follow-up Wired article.

“Cameras will record everything they do during a trip to Washington, D.C., and global-positioning satellite locators will track where they go,” Shachtman wrote. “Biomedical sensors will monitor their health. All the e-mail they send, all the magazines they read, all the credit card payments they make will be indexed and made searchable.”

The writing was on the wall. In February 2004, then-DARPA director Tony Tether cancelled LifeLog. “Change in priorities,” agency spokesperson Jan Walker explained.

Gage was in the middle of evaluating proposals and preparing to hire researchers when Tether pulled the plug. “I think he had been burnt so badly with TIA that he didn’t want to deal with any further controversy with LifeLog,” Gage told me. “The death of LifeLog was collateral damage tied to the death of TIA.”

“Canceling it was the path of least resistance,” Aftergood added.

Not long after LifeLog’s demise, Gage’s contract came up for renewal. “Tony elected not to extend my appointment,” said Gage, now retired from government service. In the time since, he’s done some part-time consulting and taken up sailing and choral singing.

Absent Gage, aspects of LifeLog might have survived, albeit under a different name. “It would not surprise me to learn that the government continued to fund research that pushed this area forward without calling it LifeLog,” Lee said. As far as we know, nothing came of DARPA’s A.I. secretary.

It was the private sector, not the government, that is coming close to turning Gage’s LifeLog, Bell’s MyLifeBits and Bush’s Memex into reality for millions of people. And ironically for privacy advocates, we practically beg for it.

In 2004, Mark Zuckerberg and Eduardo Saverin founded Facebook. Three years later, Apple introduced the iPhone. Aftergood described smartphones and social media as “LifeLog equivalents.”

More recently, wearable devices and smart-home systems like Alexa have accelerated our acceptance of digital life logs, according to Lee. “I think that Facebook is the real face of pseudo-LifeLog at this point,” Gage said.

But LifeLog’s creator said he avoids the all-seeing social network. “I generally avoid using Facebook, only occasionally logging in to see what everyone is up to, and have never ‘liked’ anything.”

His caution is understandable. Both Facebook and Apple have come under fire for gathering users’ data and passing it along to the government. “We have ended up providing the same kind of detailed personal information to advertisers and data brokers and without arousing the kind of opposition that LifeLog provoked,” Aftergood said.

Gage, for his part, said he’s devised his own LifeLog surrogate using Apple's iCalendar. “I misuse iCal as my diary, and have waded through my travel records and copious piles of personal and professional memorabilia to fill in my past timeline—but, of course, it gets ever more sparse the farther back I go,” Gage told me.

“I would like to tie all my photos into this in a coherent fashion, but I really don’t know how,” Gage added. “I want my LifeLog!”

But the public has rejected military-developed, government run digital life records in favor of similar systems developed and run by corporations. It doesn’t seem to matter to most people that the corporate social media watch them arguably as much as a government system would have.

And the government mines social media for people’s data, anyway. In October 2016 the American Civil Liberties Union revealed that police had been working with a company called Geofeedia to track peaceful protesters on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Meanwhile, Silicon Valley firm Palantir set up a “predictive policing” system in New Orleans that helped authorities anticipate potential gang ties between social media users and predict when those suspected gang members might perpetrate crimes.

Apps from Geofeedia and Palantir and other surveillance tools largely tap into data that people voluntarily share on social media. LifeLog reflected people’s growing willingness and ability to keep a comprehensive digital record of their lives—and the government willingness and ability to capture those records—more than it drove those trends.

“The growing digitization of all kinds of personal transactions, combined with the feasibility of collecting and interpreting the resulting data,” Aftergood said, “made something like LifeLog conceivable if not inevitable.”

This story originally appeared in Vice. Read more:

Black & Defiant

by SEBASTIEN ROBLIN In September 1917, Eugene Bullard was at the controls of his Spad biplane, flying a patrol over Verdun in northern France with the French air force’s N.85 Escadrille. Thousands of feet above a war-torn moonscape of trenches, barbed wire and craters, the pilot later dubbed “Black Swallow of Death” spotted a formation of blood-red, tripl…